The GEF’s RBM system is designed to capture the outcomes of GEF activities, enhance management effectiveness, and strengthen accountability. It aims to achieve these objectives by setting realistic targets, monitoring progress, integrating lessons learned into decision-making, and reporting on performance.

This section draws on the IEO evaluation of the performance of key components of the RBM system conducted during GEF-8 (GEF IEO forthcoming-d). These components include the GEF Portal, the Results Measurement Framework—particularly indicators for assessing project cycle efficiency—Agency self-evaluations, and the reporting of project results and process indicators. The evaluation also examined monitoring and evaluation (M&E) practices in fragile, conflict-affected, and violent (FCV) contexts.

The GEF Portal has made progress in automating core processes and aligning with evolving policy requirements, but still lags behind peer systems, limiting its effectiveness as a project management and reporting tool. Key business functions—such as project reviews, approvals, and Chief Executive Officer (CEO) endorsements—have been automated and updates introduced to accommodate integrated program workflows, child project reviews, and Global Biodiversity Framework Fund procedures. Training and support from the World Bank’s Information and Technology Solutions team have helped Agency users navigate the system, but resource constraints have delayed long‑requested enhancements, such as more flexible reporting and analytics capabilities. Shifting priorities—such as integrating new risk-related templates under the GEF risk appetite framework—have aligned the portal with current policy needs but slowed the automation of administrative actions, including project suspensions and amendments.

Despite improvements in data validation that have strengthened compliance and efficiency, usability challenges persist. Users report issues such as unclear error messages, limited formatting options, and a lack of automated notifications. Although features like geolocation tools and Agency fact sheets have been added, the portal is still seen as less user‑friendly and efficient than comparable systems, notably the Green Climate Fund’s portal. Many Agencies continue to maintain parallel data systems because the GEF Portal provides limited consolidated reporting, requiring them to manually combine data from multiple sources. Overall, progress is viewed as incremental, and stakeholders emphasize the need for a more streamlined, user‑centered design to meet growing operational and reporting demands.

Structural challenges persist in results measurement, despite progress made in GEF-8. During GEF-8, steps were taken to improve the GEF Results Measurement Framework, particularly to enhance clarity and ensure more consistent reporting of core indicators. Despite these efforts, several long-standing challenges remain. The GEF IEO’s 2021 Annual Performance Report identified key gaps in coverage, such as the exclusion of outcomes related to urban biodiversity and ecosystem services, and an overemphasis on physical outputs rather than systemic change (GEF IEO 2023a). It also flagged issues like the inability to measure actual restoration outcomes during project implementation, the risk of double counting geographic areas, and the lack of baseline data to assess net environmental effects. Additional concerns included inconsistencies in counting beneficiaries and long feedback loops that limit the utility of results data for real-time decision-making. While some of these concerns have been addressed in GEF-8, others continue to affect the framework’s overall effectiveness. GEF‑8 has addressed some of these concerns through clearer indicator definitions and reporting guidance, but others—particularly those related to coverage gaps, baseline data, and outcome tracking—continue to limit the overall effectiveness of the framework.

Revisions to indicators and guidance have strengthened clarity and consistency. Improvements to core indicators and accompanying guidance in GEF-8 have helped promote greater consistency in reporting and interpretation across the portfolio. A zero-baseline approach was adopted to better capture net project effects, and indicator definitions were refined to reduce overlap—such as the shift from “area of land restored” in GEF-7 to “area of land and ecosystems under restoration” in GEF-8. The adoption of SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, time-bound) criteria further enhanced clarity and practicality. First introduced in GEF-7, the core indicator guidelines were updated in GEF-8 with greater detail and alignment to corporate learning. Corporate effectiveness reporting, initiated in 2020, was further strengthened in this period as well. The GEF-8 framework places greater emphasis on adaptive management, encouraging midterm reviews to be used not only for accountability but also to support learning and improve outcomes during implementation.

Most project objectives and outcomes were supported by adequate indicators and were reported on at completion using consistent units. Each project has its own results framework, which defines project-specific objectives, outcomes, and indicators. These frameworks are aligned with the overall GEF Results Measurement Framework, which provides a standardized set of core indicators and reporting expectations for the entire portfolio. In the reviewed sample, 79 percent of project objectives and outcomes were assessed as having indicators adequate to measure achievement, and Agencies reported on 88 percent of these indicators using consistent units. However, reporting rates varied: Conservation International, United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), and the World Bank exceeded 90 percent, while others lagged behind.

Reporting on GEF core indicators—standardized metrics required across all projects—was slightly stronger. Overall, 92 percent of these indicators were reported as using consistent units, compared to 87 percent for noncore indicators. This finding reflects an increasing emphasis by GEF Agencies on standardized measurement, although comprehensive and uniform reporting across all indicators has not yet been achieved. Reporting rates were also higher for full-size projects (91 percent) than for other project types (85 percent), suggesting more consistent monitoring in larger interventions.

Critical gaps remain in capturing co-benefits, systemic change, and cost-effectiveness. Notably, many ecosystem-based projects generate adaptation co-benefits that are not adequately captured by current core indicators. While some of this information exists at the project level, the lack of standardization and aggregation makes it difficult to report comprehensively at the corporate level. In addition, the framework continues to struggle with tracking nonplace-specific ecosystem services and long-term systemic changes. The IEO’s 2021 Annual Performance Report also noted a lack of consistent data on the costs associated with generating environmental benefits, limiting the GEF’s ability to assess value for money and set realistic targets (GEF IEO 2023a). Finally, because the GEF’s results system is tied closely to specific project phases, it does not effectively measure transformational change or sustained long-term impact.

The GEF has established appropriate indicators to track operational efficiency, but the current method for defining cohorts to compare performance does not reliably capture trends. Efficiency indicators—such as the percentage of projects making their first disbursement within 18 months or submitting their midterm review within four years of CEO endorsement or approval—are currently based on the fiscal year in which these actions are reported, rather than the fiscal year of project endorsement or approval. This method may not accurately capture change because each year’s data include projects endorsed by the CEO over a wide range of years, not just those for which the monitored threshold has recently elapsed and the share meeting the threshold can be calculated (figure 11.1a). Moreover, using the fiscal year of midterm review submission can overstate the share of projects meeting the threshold by excluding those that never submit a midterm review (figure 11.1b). Tracking by fiscal year of action pools projects endorsed or approved at different times, complicating year-over-year comparisons. The IEO’s RBM evaluation found that calculating the percentage of projects meeting thresholds based on their endorsement or approval year would better capture delays within each cohort and reveal clearer patterns in meeting the monitored thresholds.

The self-evaluation system for GEF Agencies is a core component of the GEF’s RBM framework, enabling the Agencies to assess project performance and outcomes. These self-evaluations assess relevance, effectiveness, efficiency, sustainability, and lessons learned, and are guided by standardized GEF criteria. This information is conveyed by the Agencies primarily through project terminal evaluations and midterm reviews, and annual project implementation reports (PIRs). Terminal evaluations are required for all full-size projects and many medium-size projects, and are reviewed by the GEF IEO for quality and consistency.

The GEF Secretariat has taken several steps to strengthen self-evaluation for learning and adaptive management. In its 2022 Guidelines on the Implementation of the GEF-8 Results Measurement Framework, the GEF established requirements for midterm reviews and set a four-year threshold after CEO endorsement to monitor timely submissions (GEF 2022c). A good practices report outline has been circulated to Agencies, and findings from midterm reviews are synthesized in the monitoring report for corporate-level analysis. To facilitate learning, the Secretariat developed templates to document lessons learned—compiling over 1,700 by March 2023—and it conducts regular bilateral exchanges with the Agencies. The annual GEF monitoring report also prioritizes qualitative insights, highlighting adaptive management, good practices, and risk assessments to guide operational improvements.

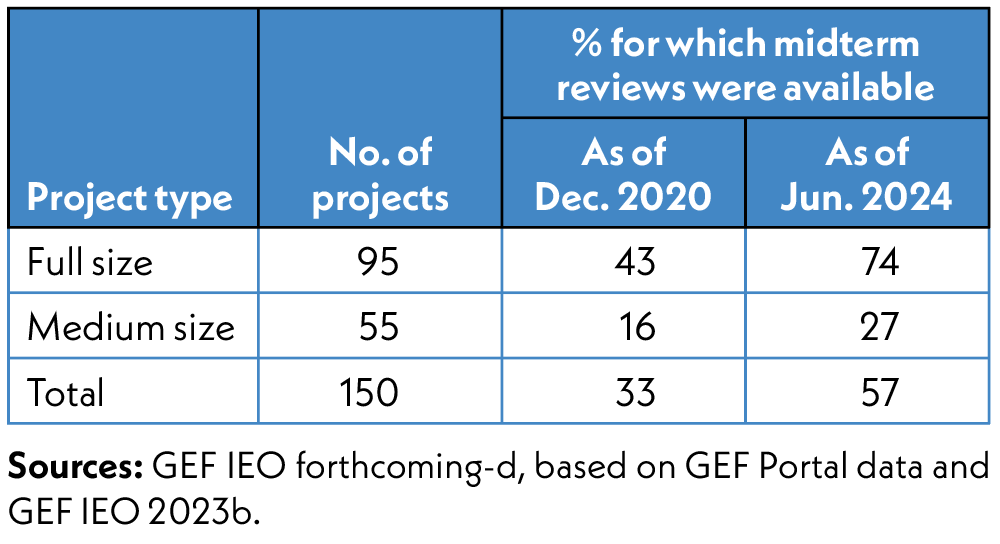

The availability of midterm reviews has improved with enhanced tracking by the GEF Secretariat; variations persist in their preparation and timing across Agencies. The RBM evaluation found that actions taken by the GEF Secretariat have significantly improved the submission of midterm reviews for full-size projects, although timely completion remains a challenge. By 2024, retroactive submissions by Agencies substantially increased the availability of midterm reviews (table 11.1). The evaluation also found that for the more recent cohorts of GEF projects for which midterm reviews may be expected—those CEO endorsed from FY2016 to FY2019—midterm reviews were submitted within four years of endorsement for 38 to 51 percent of projects. Compared to other GEF Agencies, midterm review submissions by the World Bank and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) tend to be timely.

The timeliness and availability of terminal evaluations vary across projects and Agencies. Terminal evaluations for GEF projects approved from GEF-5 onward and completed by December 31, 2023, are available for 89 percent of completed projects for which they were expected, but only 70 percent were submitted within one year of project completion. Full-size projects show better submission rates and timeliness (92 percent submitted, 74 percent on time) compared to medium-size projects (84 percent submitted, 64 percent on time). Global and regional projects, as well as those in Africa and least developed countries, exhibit lower rates of timely submission than national projects. Substantial variation exists across Agencies: Conservation International, FAO, the Inter-American Development Bank, the International Union for Conservation of Nature, and UNDP have high submission rates; the Asian Development Bank, the African Development Bank, the International Fund for Agricultural Development, and the United Nations Environment Programme lag. Timeliness is notably higher for Conservation International, FAO, and UNDP; and lower for the Asian Development Bank, the International Fund for Agricultural Development, and the United Nations Environment Programme. Joint projects involving multiple Agencies also face greater delays. Delayed submissions correlate with weaker M&E implementation but show no link with other performance metrics such as outcomes or sustainability, indicating that operational challenges rather than reluctance to report may underlie the delays.

Candor in self-evaluation remains an issue within the GEF partnership. While 73 percent of terminal evaluations are rated satisfactory or higher based on well-substantiated performance data, the reliability of earlier self-assessments—such as PIRs and midterm reviews—raises concerns. A comparison of development objectives ratings in final PIRs with independently validated outcome ratings in terminal evaluations reveals a notable discrepancy: 96 percent of projects received satisfactory range ratings in PIRs, but only 87 percent maintained this rating after independent validation. In 10 percent of cases, PIR ratings were inflated by two grades relative to terminal evaluations. These discrepancies suggest ongoing limitations in reporting objectivity, echoing findings from a previous evaluation of GEF self-evaluation systems, which identified a lack of institutional incentives for candor (GEF IEO 2023b). However, some Agencies are beginning to foster a more transparent evaluation culture. For example, the Inter-American Development Bank has created a Development Effectiveness Unit, which supports projects from design to postevaluation and seeks to ensure that evaluation results are used to inform country strategies and project cycles.

Projects in FCV contexts represent a significant portion of the GEF portfolio, and M&E in such contexts faces unique and persistent challenges. Projects in FCV contexts often operate under conditions that differ from more stable environments, yet these distinctions are not fully reflected in the current GEF Results Measurement Framework. Although FCV countries represent 26 percent of GEF recipients and account for 20 percent of GEF-8 System for Transparent Allocation of Resources (STAR) allocations, the framework offers limited guidance on how to address FCV-specific challenges. Moreover, although the GEF Policy on Environmental and Social Safeguards (GEF 2018b) includes basic requirements related to conflict management, it does not provide detailed direction for conflict-sensitive monitoring. As a result, many projects in FCV areas do not include objectives or indicators tailored to sociopolitical dimensions such as community collaboration or perceptions of security. To support more context-appropriate project design and reporting, the framework could be enhanced by integrating indicators related to social cohesion, adaptive practices, and inclusive consultation processes. Such adjustments would help improve the relevance and utility of M&E in FCV settings.