This chapter presents evaluative evidence on integrated programming in the GEF, highlighting its importance for driving transformational change and generating environmental benefits at scale. Drawing on earlier IEO reviews of integrated programming (GEF IEO 2018c, 2022d), as well as evaluations of the Sustainable Forest Management, Global Wildlife, Food Systems, and Sustainable Cities programs (GEF IEO 2022e, forthcoming-e, forthcoming-k, forthcoming-n), the chapter examines whether and how integrated programming delivers value beyond traditional stand‑alone projects. It focuses not only on operational, institutional, and policy‑level results, but also on the role of knowledge platforms and coordination mechanisms—a core feature of integrated programming—in catalyzing systemic shifts.

Integrated programming was designed to be additional to previous approaches, supporting systemwide solutions capable of tackling the complex drivers of environmental degradation and enabling transformational change. This chapter discusses the evolution of the portfolio of integrated programming as well as the relevance, governance, effectiveness, efficiency, inclusion, knowledge platforms, sustainability, and scaling of these programs. In covering these topics, the IEO has adopted a six‑domain framework (box 6.1) derived from its Evaluation of GEF Support for Transformational Change (GEF IEO 2018b). Together, these domains—(1) a systems-based vision for transformational change; (2) implementation quality and results; (3) ambition, innovation, and adaptation; (4) stakeholder inclusion; (5) sustainability and scale-up; and (6) knowledge sharing—frame how integrated programming can amplify the GEF’s ability to generate environmental benefits at scale while delivering socioeconomic co‑benefits and strengthening institutions for long‑term resilience. This chapter, following an overview of the GEF’s integrated programming portfolio’s evolution and governance, is organized roughly along these six domains.

The GEF has increasingly placed inclusion at the center of its programming, recognizing that environmental results are more effective and sustainable when all voices—especially those of women, Indigenous Peoples, youth, persons with disabilities, and other historically marginalized groups—are meaningfully engaged. Inclusion is not only a matter of equity, but also a catalyst for transformational change, as it enhances local ownership, brings diverse knowledge systems into decision-making, and strengthens the sustainability of environmental interventions.

As part of this approach, the GEF Secretariat has, in recent years, prioritized strengthening its engagement with groups that have historically faced marginalization or vulnerability, among them women, Indigenous Peoples and local communities (IPLCs), youth, and persons with disabilities. This commitment is advanced through multiple channels, including GEF policies and safeguards on gender equality and stakeholder engagement, which set minimum standards across the portfolio. Inclusion is also operationalized through delivery mechanisms such as the Small Grants Programme (SGP) and community-based approaches (CBAs), which directly support civil society and locally led action. The SGP enables grassroots participation through tailored grantmaking, while CBAs work to integrate local knowledge and priorities into larger-scale GEF initiatives. Together, these instruments reflect the evolving orientation of the GEF toward more inclusive, equitable, and locally responsive environmental programming.

This chapter examines how the GEF is advancing inclusion through its policies, safeguards, and delivery mechanisms. It draws on a portfolio analysis of 300 GEF projects—representing $1.2 billion in GEF funding and $6.7 billion in cofinancing—to assess the inclusion of marginalized groups, with particular attention to fragile and conflict-affected situations, where these groups face heightened vulnerability and disproportionate impacts from environmental and socioeconomic shocks.1 It also incorporates findings from evaluations of CBAs and the SGP (GEF IEO 2024a, forthcoming-c), which are important delivery mechanisms for reaching and empowering marginalized populations at the local level.

The GEF has a series of measures to ensure inclusion in GEF-funded projects: GEF policies on environmental and social safeguards, gender equality, and stakeholder engagement; review and feedback from the GEF Secretariat during the design stage on issues related to inclusion; and a self-tagging system for projects to identify their early consideration of marginalized groups.

Private sector engagement has become increasingly relevant to the GEF, stemming from the recognition that global environmental challenges and the advancement of transformational change cannot be addressed by public sector efforts alone. Drivers motivating the private sector to engage with the GEF include corporate strategies, the alignment of business targets with multilateral environmental agreements, regulatory frameworks, investor requirements, and evolving disclosure and reporting standards. Additional momentum is provided by private sector roadmaps and global initiatives for net-zero and nature-positive outcomes. Innovation—often led by private actors—remains a central motivator, alongside the opportunity to mobilize additional capital through blended finance.

The GEF has used nongrant instruments (NGIs) since its inception.1 A dedicated NGI set-aside was first introduced in GEF-4 and later evolved into a dedicated NGI funding window, known in GEF-8 as the Blended Finance Program. In addition, NGIs can be used under System of Transparent Allocation of Resources (STAR) allocations, in the international waters or chemicals and waste focal areas, and under the Global Biodiversity Framework Fund. While NGIs are designed to stimulate private finance, their portfolio remains small. Meanwhile, grant-based support—which can help create enabling environments, support early-stage innovations, and strengthen institutional capacity—remains the GEF’s dominant modality in engaging the private sector.

The GEF’s Private Sector Engagement Strategy (PSES) identifies two pillars for the private sector to engage with the GEF. These are (1) through the use of blended finance, or NGIs; and (2) as an agent for market transformation to shift business practices through reforms, value chain improvements, and sectorwide collaboration (GEF 2020). However, the PSES lacks measurable targets, limiting ability to assess progress or evaluate the effectiveness of its intent.

In practice, the GEF implements both approaches. It engages the private sector by de-risking and catalyzing investments that would otherwise be constrained by market failures, regulatory weaknesses, or unfavorable risk return profiles. It provides concessional, risk-bearing capital through blended finance to support ventures unable to access commercial funding, thereby unlocking innovation and enabling the scaling of solutions with global environmental benefits. Through market transformation efforts such as policy reform, awareness raising, and capacity building, the GEF helps establish conditions for businesses to adopt more sustainable practices.

The GEF has fully implemented the private sector engagement recommendations from the Sixth Comprehensive Evaluation of the GEF (OPS6) and made partial progress on those from OPS7. In response to OPS6, it adopted systems approaches by partnering with financial institutions to de-risk investments, structure innovative finance, and influence industry practices through certification, research, and sustainable supply chains. Progress on OPS7 recommendations—narrowing the focus of engagement, clarifying the value proposition, and better integrating financial and nonfinancial support, including for micro, small, and medium enterprises—remains ongoing.

This chapter reviews the portfolio of GEF projects featuring private sector involvement (here referred to as private sector projects), looks at the effectiveness of such projects, describes the GEF’s strengths in engaging the private sector, and outlines some constraints to further private sector integration in GEF projects and operations. It draws on the recent IEO evaluation of private sector engagement (GEF IEO forthcoming-f).

As global environmental challenges intensify, the ability to manage risk while fostering innovation is increasingly essential for achieving meaningful and lasting impact. For the GEF, the rationale for supporting innovation—particularly through the use of advanced technologies—has never been more compelling. These tools offer the potential to address complex and systemic threats, such as climate change, biodiversity loss, and pollution at scale, where conventional solutions might be insufficient.

To address this need, the GEF has made notable institutional shifts. The GEF-8 Strategic Positioning Framework emphasized innovation as a key driver for transformational change (GEF Secretariat 2022b), supported by the establishment of an Innovation Window and reinforced by the adoption of the 2024 risk appetite statement, which assigns the GEF a high appetite for innovation risk (GEF 2024b; STAP 2022). These developments signal a clear commitment to enabling calculated risk-taking and forward-looking solutions designed to accelerate systemic change.

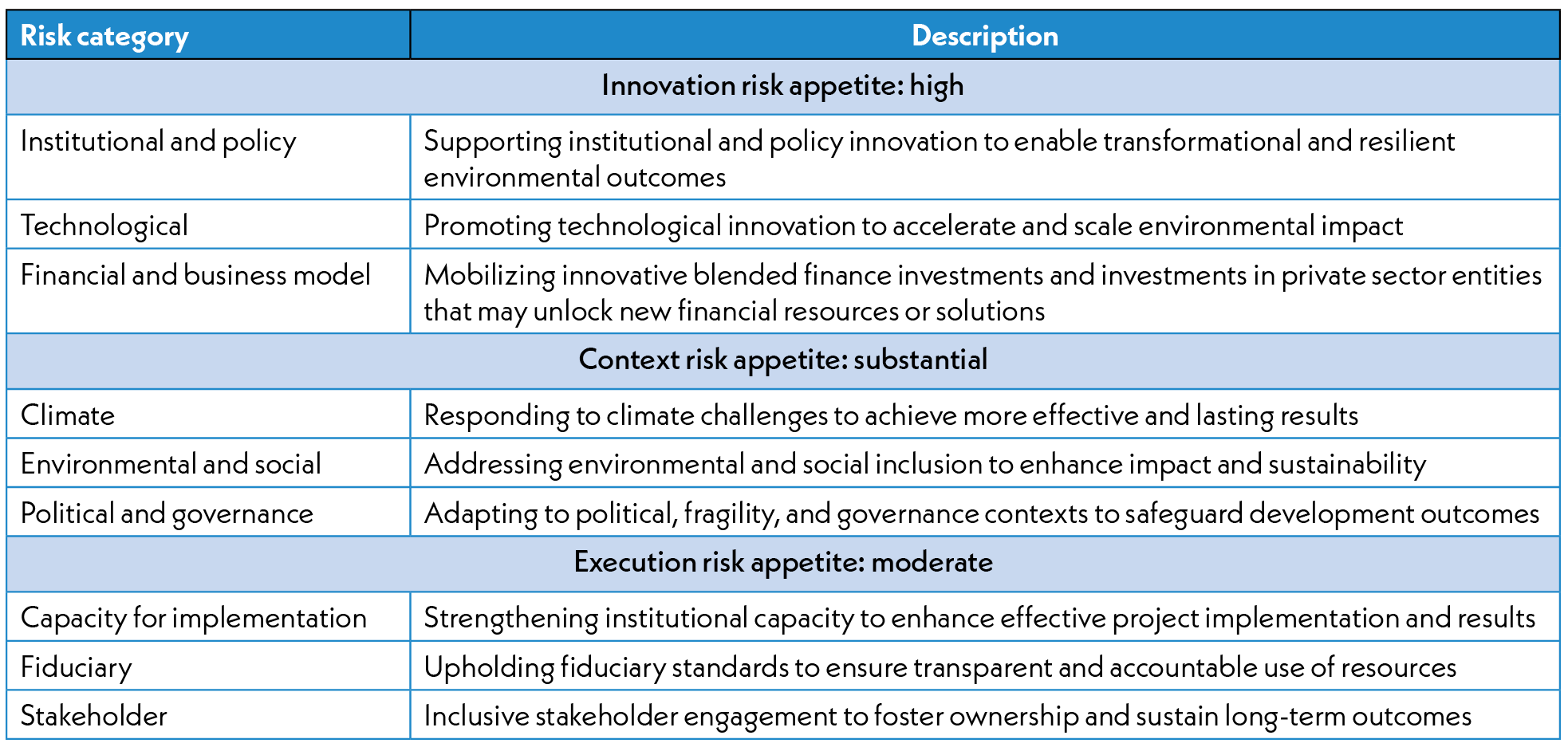

Risk management in the GEF, however, extends well beyond innovation. Projects must also navigate contextual risks, including climate variability, environmental and social safeguards, and shifting political or governance conditions, as well as execution risks, such as fiduciary oversight, institutional capacity, and challenges to stakeholder engagement. Recognizing these diverse challenges, the GEF Council adopted a risk appetite framework to guide Agencies in taking calculated risks. This framework differentiates risk appetite across three dimensions: innovation risk (high), contextual risk (substantial), and execution risk (moderate). By applying differentiated appetite levels, the framework supports adaptive risk management and learning, enabling projects to pursue systemic and scalable outcomes while maintaining robust mitigation measures (table 9.1).

The GEF places particular emphasis on innovation risk, recognizing that transformational change often requires testing unproven solutions. This risk encompasses three areas: institutional and policy risks, arising from political or regulatory shifts; technological risks, linked to the uncertain performance of new or unproven technologies; and financial and business model risks, reflecting the challenges of attracting private investment to novel instruments such as biodiversity credits or blended finance.

While many successful approaches combine different types of innovation, this chapter focuses on technological innovation and its associated risks, reflecting both its high rating in the GEF risk appetite statement and its potential to deliver quick, tangible outputs and attract private sector engagement. Recent years have seen an exponential pace of technological advancement, offering unprecedented opportunities to address environmental challenges at scale. Scientific and policy assessments (e.g., Bierbaum et al. 2024; Lenton et al. 2023; World Economic Forum 2017, 2020, 2021) highlight technological innovation as a key enabler of transformational environmental management, from reducing greenhouse gas emissions and improving natural resource efficiency to curbing pollution and boosting agricultural productivity.

Against this backdrop, this chapter examines risk in the GEF portfolio broadly, with a focus on technological innovation. It draws on two recent evaluations—Assessing Portfolio-Level Risk in the GEF and Evaluation of Innovation and Application of Technologies in the GEF (GEF IEO forthcoming-b, forthcoming-l)—to explore how risk and innovation ambitions are being translated into practice, what enabling conditions are needed, and which barriers remain.