Integrated programming is aligned with the objectives of global environmental conventions and GEF focal areas. Table 6.1 presents the expected contribution of each program to these focal areas, indicating the degree of alignment. Some programs—Food Systems, the Net-Zero Nature-Positive Accelerator, Greening Transportation Infrastructure, Ecosystem Restoration, and Circular Solutions to Plastic Pollution—are designed to contribute across nearly all focal areas. Others—Sustainable Cities, Wildlife Conservation for Development, and Clean and Healthy Ocean—have a more focused thematic scope.

GEF integrated programming is highly relevant to GEF strategic priorities and global environmental challenges, applying systems thinking to link global drivers of degradation with country‑level solutions and stakeholder dynamics. Child projects are increasingly designed to address underlying pressures—such as commodity value chains, urbanization, and illegal wildlife trade—through integrated interventions tailored to local contexts. The Global Wildlife Program (GWP), for example, evolved from an initial focus on illegal wildlife trade to a broader systems approach that also addresses human-wildlife conflict, zoonotic diseases, and community‑based wildlife economies. Projects such as South Africa’s Strengthening Institutions, Information Management, and Monitoring to Reduce the Rate of Illegal Wildlife Trade (GEF ID 9525, United Nations Environment Programme [UNEP]) and Botswana’s Managing the Human-Wildlife Interface to Sustain the Flow of Agro‑Ecosystem Services and Prevent Illegal Wildlife Trafficking in the Kgalagadi and Ghanzi Drylands (GEF ID 9154, United Nations Development Programme [UNDP]) illustrate cross‑sectoral collaboration spanning agriculture, forestry, energy, water, and urban planning.

Similarly, Sustainable Cities has emphasized integrated urban planning, capacity development, and the promotion of environmentally friendly policies and regulatory frameworks. National knowledge platforms, such as those established in Brazil, India, and Malaysia, and city‑level planning processes have enabled diagnostic analyses, long‑term strategies, and targeted priority actions. These interventions address institutional capacity gaps through training programs while promoting sustainable urban development and generating direct environmental benefits at the local level. Although linkages across child projects remain limited, participation in global platform workshops has facilitated cross-learning and contributed to gradually increasing program coherence.

Under the food systems theme, the GEF’s strategic direction has focused on addressing key drivers of food systems transformation and promoting value chain approaches. While these programs target systemic drivers—including environmental, political, economic, sociocultural, individual, and technological factors—and emphasize levers of change such as governance, finance, multistakeholder dialogue, and innovation, most child projects have concentrated primarily on the production segment. Sociocultural drivers, such as dietary preferences, social norms, and food traditions, have received limited attention.

The IAPs in GEF‑6, followed by the FOLUR Integrated Program (GEF‑7) and the Food Systems Impact Program (GEF‑8), progressively adopted a value chain perspective. However, under GEF‑7 and GEF‑8, 92 percent of child projects focused on production, while other value chain segments received far less emphasis: postproduction and storage (17 percent), processing (37 percent), aggregation (12 percent), distribution (31 percent), and consumption (10 percent). Integration of traditional knowledge was also limited, with only 9 percent of projects explicitly incorporating it in their design, reducing opportunities to embed local practices into culturally grounded and systemic solutions.

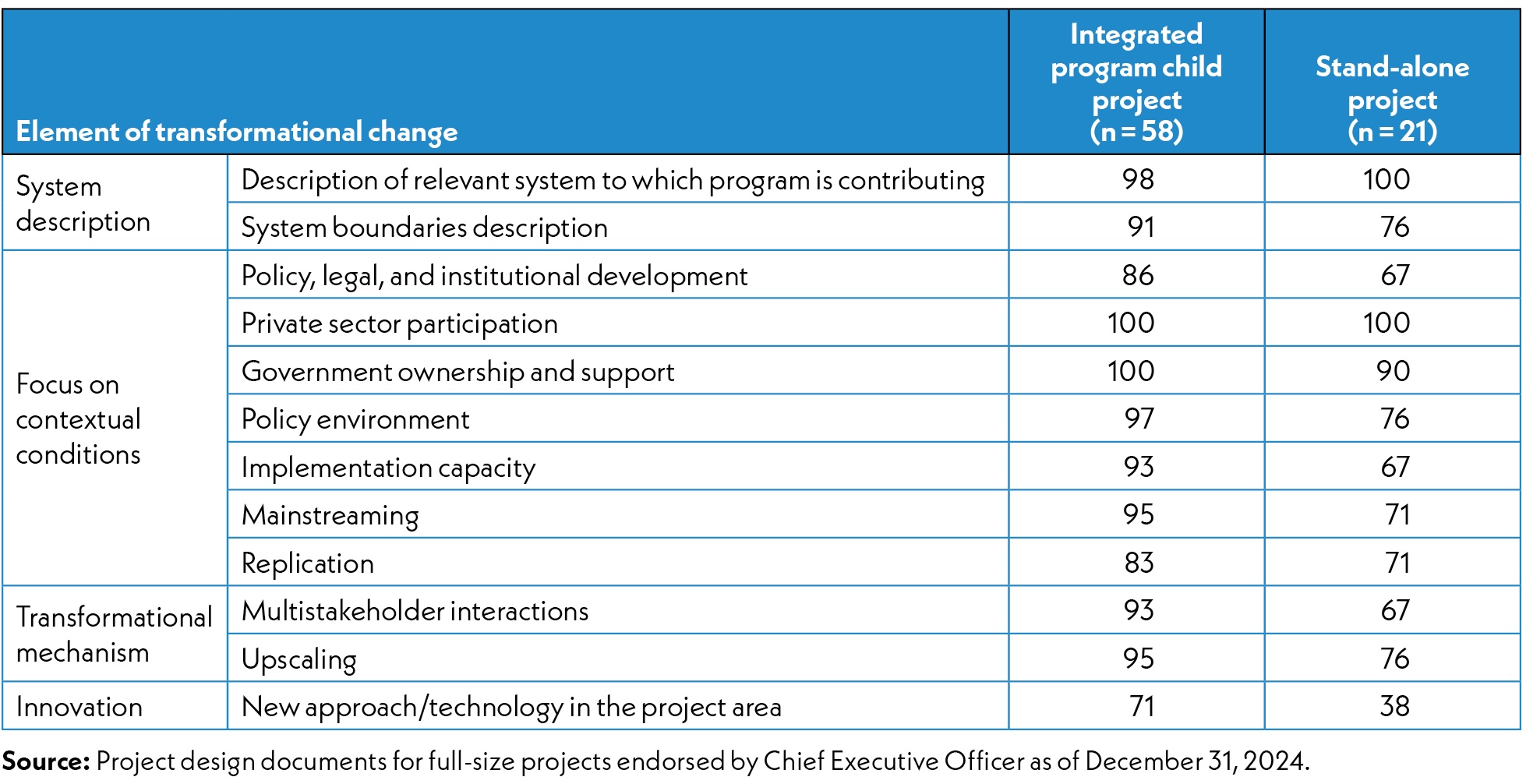

Under GEF‑8, integrated program child projects were more likely than stand‑alone projects to incorporate design features that enable transformational change. This tendency reflects strong alignment with GEF strategic priorities to address environmental challenges at scale. A review of 58 integrated program child projects and 21 stand‑alone projects (table 6.5) found that, while both modalities included elements such as knowledge exchange, capacity development, and systems‑level perspectives, integrated program projects more consistently defined system boundaries; addressed contextual, policy, and capacity gaps; and embedded mechanisms for scaling, mainstreaming, and replication. They also demonstrated stronger multistakeholder engagement and institutional coordination (discussed further in section 6.7). In terms of innovation (discussed further in section 6.6), integrated program child projects introduced new or less common approaches and technologies in 71 percent of cases, compared with 38 percent of stand‑alone projects. Collectively, these features advance the GEF strategy to tackle the drivers of environmental degradation through integrated, multisector solutions, enhancing the potential to deliver global environmental benefits at transformational scale.

Despite the positive attributes of integrated programming, the expansion to 11 integrated programs in GEF‑8 has introduced risks that could undermine long‑term relevance if not effectively managed. Coordination demands both within and across programs have increased significantly, with each program averaging 18 child projects and 17 participating countries, while average financing per child project declined by 20 percent. These factors make it more challenging to maintain program coherence and alignment with strategic objectives. The scale‑up from 3 to 11 programs has also heightened the need for cross‑program coordination—yet links between programming phases remain weak, underscoring the importance of realistic interreplenishment planning. Furthermore, when programs are discontinued, the absence of clear exit strategies risks undermining continuity and long‑term impact, potentially diminishing the sustained relevance of integrated programming.