Managing risk has become increasingly important for development organizations over the past decade, particularly in the face of global environmental degradation and other complex challenges. In response, many GEF Agencies have developed enterprise risk management frameworks. These frameworks are intended to help optimize resources and achieve impact, even when these actions involve taking on higher levels of risk. Transparency and strategic risk-taking have become central to these efforts.

Recognizing the need to adopt more deliberate risk-taking in pursuit of innovation and global environmental benefits, the GEF Council approved a risk appetite document at its 66th meeting. This document is intended to guide Agencies in taking calculated risks while maintaining prudent management (GEF 2024b). It also signals a shift in the GEF’s approach to managing risk and fostering innovation. For this shift to take hold, the GEF must define its desired portfolio-level risk, clarify risk tolerance, and ensure shared understanding of risk ownership. Internal risk management processes within the GEF will also need to evolve to support these changes.

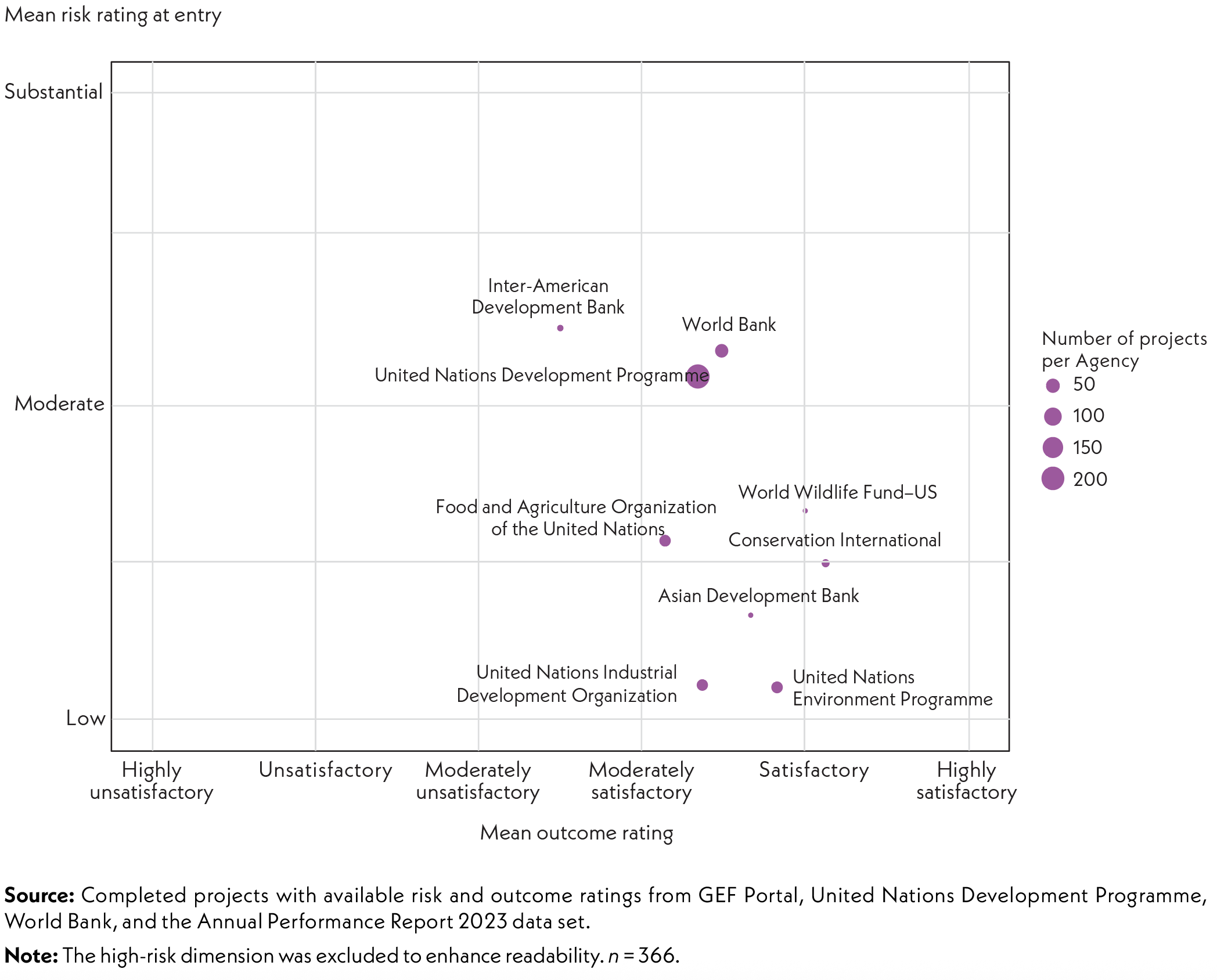

The GEF portfolio is currently characterized by a low to moderate risk profile. The evaluation considered multiple dimensions of risk, including political and governance conditions in the context of fragility, capacity for implementation and adaptive management, and fiduciary risk. Innovation risk was a prominent factor, looking at risks associated with institutional and policy changes, new financial and business models, and the adoption of advanced technology. Most projects are rated as low risk and have delivered outcomes rated in the satisfactory range (figure 9.1). Data from 366 closed projects show that the largest share is clustered around low-risk projects with satisfactory range results. Projects rated as high risk with at least marginally satisfactory outcomes represent a smaller portion. No clear transition toward a higher risk profile has been observed across GEF replenishment periods based on closed projects to date.

Although high-risk projects make up a smaller share of the portfolio, the GEF seeks to enable greater calculated risk-taking. The cultural adjustment required to support this aspiration has yet to occur. GEF Agencies display different attitudes toward risk and use varying criteria for risk measurement and management. In many cases, their self-described risk culture does not match the data. This inconsistency points to the need for a more harmonized understanding of risk across the GEF partnership to effectively implement the new risk appetite framework. The risk document emphasizes that further consultation and clarification are needed to support this effort (GEF 2024b).

Risk ratings for child projects under integrated programs show a moderate overall risk profile, generally below the GEF’s stated risk appetite. In both the contextual and innovation dimensions, GEF‑8 projects were within the moderate risk category. For contextual risks, GEF‑8 projects were rated as substantial; for innovation, no project was rated as high despite the GEF’s high-risk appetite for innovation. For execution risks, 49 percent of projects were rated as low and 42 percent as moderate: in this domain, the GEF risk appetite is moderate.

A few projects exhibit higher risk profiles. In GEF‑8, the Enabling Large-Scale Ecosystem Restoration in Haiti through the Piloting and Implementation of Payments for Environmental Services Schemes (GEF ID 11130, United Nations Environment Programme) project and the Northern Mozambique Rural Resilience Project (GEF ID 11133, World Bank) are rated high risk across all context categories due to severe environmental degradation, insecurity, and social tensions. In innovation, no projects are rated high overall, but the Resilient Urban Sierra Leone Project (GEF ID 10768, World Bank) is rated substantial across institutional, technological, and financial risk categories, while Haiti’s ecosystem restoration project has a high institutional and policy risk rating. For execution risks, Haiti again stands out, along with the Chad ecological corridors project (GEF ID 11138, International Union for Conservation of Nature), which faces fiduciary and procurement challenges.

Projects in fragile and conflict‑affected situations carry higher risk ratings across all dimensions compared to those in more stable contexts. Compared to stand-alone, full‑size projects, integrated program child projects tend to have lower contextual and execution risk ratings, yet both groups show no high innovation risk ratings despite the GEF’s appetite for risk-taking in this area.

Across Agencies, different risk profiles can result in similar project outcomes. Some Agencies are better equipped to manage risk due to internal capacities or institutional structures, while others face more constraints (figure 9.2). Agencies tend to adhere to their own standards, which are influenced by their unique incentive structures. To shift the GEF’s overall risk profile, collaboration with Agencies is essential to build both willingness and capacity for higher-risk engagement.

High-risk projects typically exhibit greater variance in outcomes. Although a higher level of risk may sometimes be associated with lower outcomes, there are clear cases where high-risk projects have yielded significant benefits.

For example, in the climate change focal area, three high-risk renewable energy projects that focused on solar energy and policies to reduce fossil fuel subsidies achieved the highest possible outcome ratings. These projects—all led by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and conducted in Nepal, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, and Marrakesh (GEF IDs 4345, 5297, and 9567)—addressed regulatory barriers and promoted energy efficiency, demonstrating the potential rewards of targeted high-risk investments. Similarly, a high-risk protected area project in Uruguay (GEF ID 4841, UNDP) shows the benefits of long-term GEF engagement. In that project, remote sensing of the Esteros de Farrapos National Park reveals minimal forest loss within park boundaries over time, confirming the park’s effectiveness as a buffer against deforestation.

Institutional and state capacity strongly influence a project’s risk profile. Weak technical or financial capacity, limited government ownership, and low in-country capacity are major concerns. Conversely, countries with stronger institutions and rule of law tend to manage and implement projects more successfully, resulting in better outcomes.

Adaptive risk management also plays a role in influencing results. Among 315 projects that reported more than one risk rating over their implementation period, 29 percent showed a decrease in risk rating, suggesting successful mitigation or adjustment during implementation. In contrast, 13 percent of projects saw risk ratings increase, possibly due to unforeseen challenges or underestimation at design. Projects that experienced a reduction in risk ratings generally achieved better outcomes, supporting the value of adaptive management.

Most GEF projects continue to operate within a low to moderate risk profile, and there is increasing recognition of the need for greater calculated risk-taking to achieve ambitious environmental goals. Strong examples, such as solar energy and protected area projects, highlight the potential benefits of this approach. Moving toward a higher-risk, higher-reward model will require clearer internal guidance, enhanced coordination with Agencies, and a shared understanding of risk within the GEF partnership.

After examining the overall risk profile of the GEF portfolio, this section focuses specifically on the risks associated with technological innovation.

The overall risk profile of technological innovation within the GEF portfolio is low to moderate, with no evidence that projects involving technological components systematically carry higher risks. Among 2,016 projects reviewed, only 4 (0.2 percent) were classified as having substantial or high technological risks, mostly due to low adoption rates or continued reliance on outdated technologies. Risk assessment of emerging technologies is often incomplete; for example, concerns about the energy demands of artificial intelligence (AI) or the data security implications of blockchain—well-documented risks identified by the STAP and the broader literature—are rarely addressed explicitly in project design, even if the eventuality of these risks could be limited.

An exception to the portfolio’s overall low-to-moderate profile is private sector engagement projects, which tend to have higher innovation risk ratings than the rest of the portfolio. Since the adoption of the GEF risk appetite statement in 2024, private sector engagement projects have shown slightly lower contextual and execution risks but higher innovation risks, driven mainly by technological and financial model innovation (figure 9.3). Examples include the EarthRanger project (GEF ID 10551, Conservation International), which introduces private sector wildlife-monitoring software; and the low-emission vehicles project in Uzbekistan (GEF ID 10282, UNDP), which develops business models to attract private investment into a traditionally public transport sector.

Source: GEF Portal as of July 24, 2025.

Note: The risk rating for each category is based on the latest risk rating available for each project. No averaging was applied.

Despite the GEF’s stated high appetite for innovation risk, most projects remain low risk by design, because countries and agencies often prioritize proposals perceived as more likely to secure approval. These procedural and institutional constraints limit the number of projects that embrace higher-risk technological innovation, even where such approaches could deliver transformational impact.