The GEF enhances the likelihood of sustaining outcomes and achieving impact over the long term by supporting three critical areas: broader adoption of interventions by stakeholders, environmentally coherent national policies, and shifts in stakeholder behavior from environmentally harmful to environmentally friendly practices. Broader adoption, reinforced by behavior change, reflects strong stakeholder ownership that drives continued action and expands environmental benefits beyond project completion. Coherent environmental policies help create synergies and reduce trade‑offs with nonenvironmental goals that might otherwise undermine system‑level gains. By catalyzing replication and scaling of successful interventions, fostering shifts in societal norms, and aligning national and local policies with global environmental goals, the GEF helps move individual project results toward long‑term transformational change. This section reviews the extent to which completed projects are achieving broader adoption and examines how GEF‑8 projects are being designed to incorporate features that support transformational change.

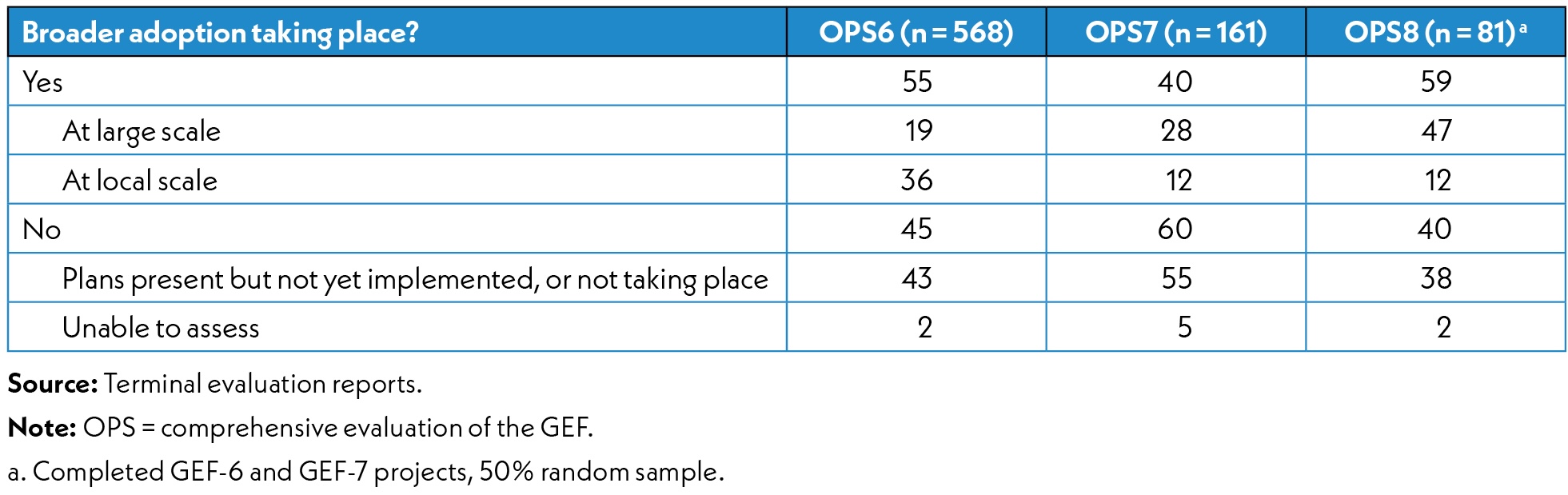

The GEF’s resources are limited; only through large-scale adoption by other actors can the GEF achieve transformational change and sustainability. Broader adoption refers to the uptake of GEF-supported interventions by stakeholders through sustaining, mainstreaming, replication, and scaling up—without the use of GEF funds. A review of completed GEF-6 and GEF-7 projects randomly sampled from a pool of 161 projects was conducted to assess the extent to which broader adoption was occurring at the time of project completion.

Fifty-nine percent of projects achieved some form of broader adoption. The most common form was the mainstreaming of enabling conditions, such as policy, legal, and institutional development (58 percent) and individual and institutional capacity building (40 percent). Examples include government adoption of national strategies or environmental laws developed with GEF support, and the institutionalization of monitoring systems into regular government operations. In contrast, broader adoption of technologies, practices, and approaches that directly generated environmental benefits—such as crop rotation or electric vehicle use—was reported in only 18 percent of projects. Climate change and multifocal area projects exhibited the highest rates of broader adoption. Compared to older cohorts, a greater proportion of more recent projects achieved broader adoption at completion, and at a larger scale. Table 3.4 provides a detailed comparison.

The Implementation of SLM Practices to Address Land Degradation and Mitigate Effects of Drought (GEF ID 5767, UNDP) project undertaken in the Philippines has been replicated by the city government using its own agriculture budget; the provincial government has also scaled up SLM efforts. At the national level, SLM has been integrated into agricultural programs, prompting additional local governments to allocate funding for further adoption.

A UNDP-led project in Uruguay provided capacity building for mercury analysis (GEF ID 4998). One pilot laboratory institutionalized the initiative by hosting biennial training for other countries. Five years after project closure, project participants continue to engage through an informal learning network spanning six Latin American countries.

In Sri Lanka, the Rehabilitation of Degraded Agricultural Lands in Kandy, Badulla and Nuwara Eliya Districts in the Central Highlands (GEF ID 5677, FAO) project, which transitioned farmer field schools online during the COVID-19 pandemic, led to increased replication of sustainable agricultural practices, particularly among women and youth. Building on this success, the government scaled up the model nationwide.

Broader adoption beyond project completion is influenced by alignment with government priorities, sustained support, and economic benefits. Initiatives aligned with national priorities were more likely to be taken up. Government uptake in turn provided continuity and long-term support through policies and budgets. Potential economic benefit was the most common motivation for broader adoption cited by different stakeholder groups.

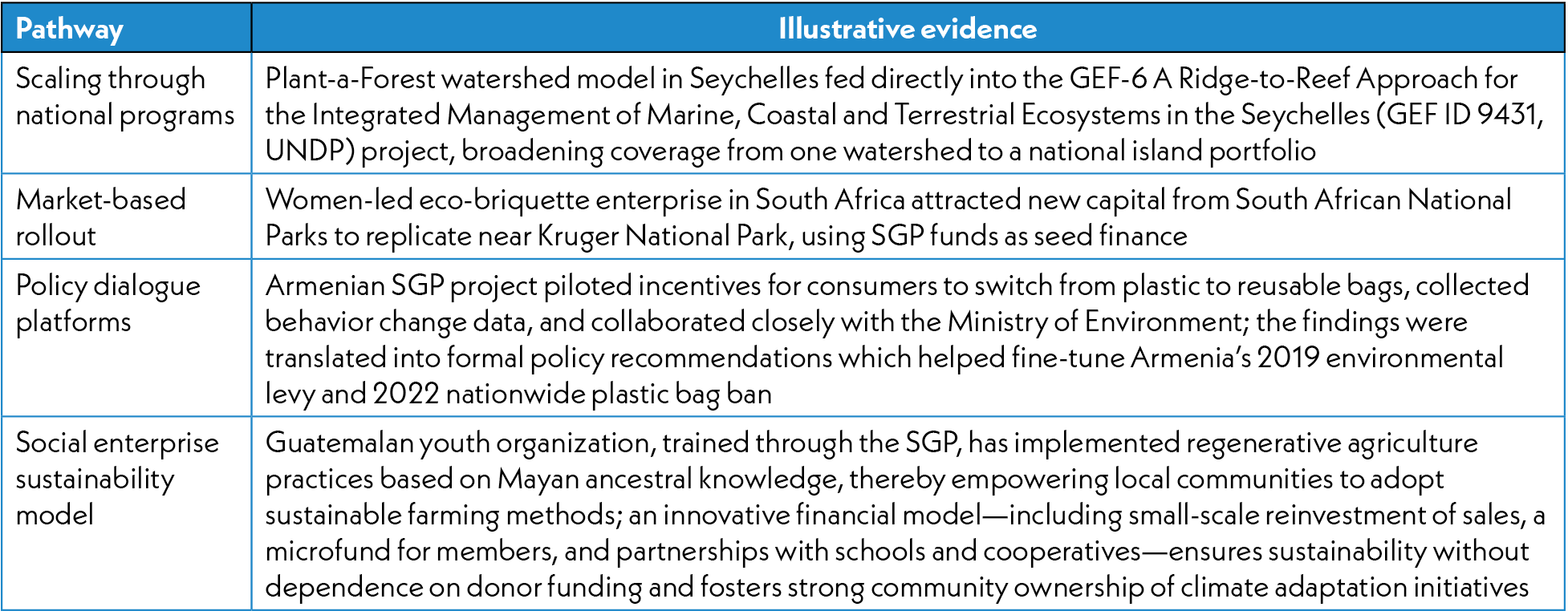

Set up as pilots or demonstration initiatives, Small Grants Programme (SGP) projects are designed to be replicated, scaled up, or integrated into broader frameworks. Common pathways for scaling include strong community ownership, capacity building, leadership development, integration into policies and institutions, and expansion through partnerships and follow-up financing. GEF SGP monitoring reports from FY 2020–21 to FY 2023–24 show that 566 completed projects (15.2 percent) have been replicated or scaled by partners. Since 2020–21, approximately 13 percent (470 projects) have influenced policy. These figures likely represent conservative estimates, as scaling and replication often occur after project completion and may be underreported. Table 3.5 provides examples of replication and scaling from SGP initiatives in practice.

Sources: SGP 2024a, 2024b; SGP Plastic Free Armenia Behavioral Change and Awareness Raising Campaign web page; UNDP Juventud Guatemalteca Lidera La Acción Climática web page.

Note: SGP = Small Grants Programme; UNDP = United Nations Development Programme.

GEF interventions often serve as a foundation for projects supported by the Green Climate Fund (GCF). The GEF’s Annual Performance Report 2025 found that of 253 projects financed by the GCF through June 2024, 17 percent indicate an intent to build on GEF projects (GEF IEO forthcoming-o). Consistent with the GCF role of providing financing at scale, in two-thirds of these instances (12 percent of the total), projects aimed to scale up GEF-supported interventions. One GCF program seeks to scale up climate adaptation initiatives originally supported through the GEF SGP in the Federated States of Micronesia, offering grants of up to $10 million per project. The program proposal emphasized that such projects were not viable for government debt financing and that only GCF support could provide funding at the necessary scale. Another GCF project builds on a pair of World Bank–implemented initiatives—funded respectively by the GEF Trust Fund and the Special Climate Change Fund (SCCF) for a combined $8.73 million—in the West Balkans Drina River Basin totaling (GEF IDs 5556 and 5723). The GCF project aims to upgrade and expand the hydrometric monitoring network while scaling up proven solutions and technologies developed under the SCCF project, among others.

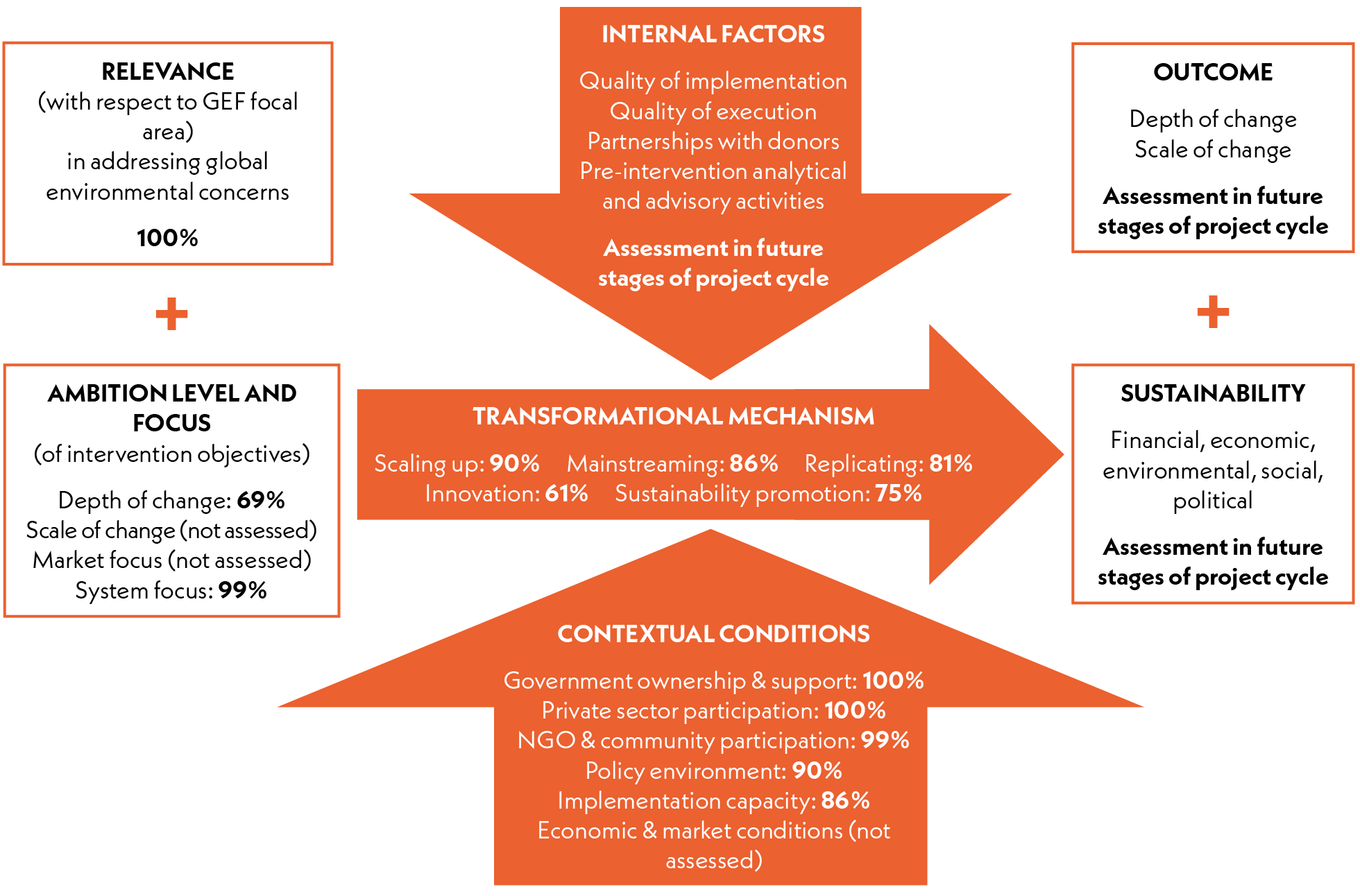

The GEF’s structured approach to transformational change is closely linked to its commitment to enabling broader adoption and scaling up of impactful solutions. Since the launch of GEF-6, the GEF has taken a more intentional and strategic approach to achieving transformational change, aiming to drive systemic shifts in key economic sectors for lasting global environmental benefits. This GEF strategy is based on four key levers: governance and policy, financial leverage, innovation, and multistakeholder dialogue. It is thus important to assess how these levers are being deployed through GEF projects. The GEF IEO introduced a theory of change framework to assess transformational interventions supported by the GEF (GEF IEO 2018b). This framework identifies relevance, ambition and systemic focus, attention to contextual conditions and actors, and transformational mechanisms as key project design areas that may contribute to transformational change.

The IEO reviewed a sample of 83 full-size GEF‑8 projects approved and endorsed by the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) through December 2024, applying its framework for assessing transformational change. The review found that nearly all projects are purposefully designed to support transformational outcomes (figure 3.6). These projects consistently align with focal area priorities, define clear system boundaries, consider contextual conditions, and outline pathways for broader adoption and scale‑up. Most also integrate key design features such as knowledge management, capacity building, stakeholder engagement, legal and policy reforms, and the piloting of innovative approaches. Notably, 60 percent of the reviewed projects include innovations or technologies that are new to the project area.

Integrated programs demonstrate greater potential than stand-alone projects to deliver transformational outcomes. This is further discussed in chapter 6.

Sources: Project design documents for random sample of 83 GEF-8 full-size projects endorsed by Chief Executive Officer as of December 31, 2024.

Note: NGO = nongovernmental organization, “CEO = Chief Executive Officer; PIF = project identification form.

The GEF-8 Programming Directions identify “governance and policies” as a key lever for system transformation (GEF Secretariat 2022a). Consequently, in October 2023, the GEF Council approved a strategic roadmap to strengthen policy coherence through projects, programs, and corporate activities. A recent IEO evaluation looked at policy coherence in terms of the alignment between environmental and other public policy objectives, or between different environmental objectives such as biodiversity and climate change, to better achieve global environmental benefits.

Emerging findings from document reviews and field-based case studies of completed projects, other IEO evaluations, and stakeholder interviews have found that while this new focus more deliberately introduces initiatives at the program and corporate levels, the GEF has historically supported the alignment of environmental and nonenvironmental goals through policy reform at the project level (GEF IEO forthcoming-j). Biodiversity mainstreaming, sustainable forest management, land degradation neutrality, and integrated water resource management are some of the focal area approaches that have worked on improving policy coherence as a means to achieve project outcomes. Completed projects show contributions to increased policy coherence between environmental and nonenvironmental sectors, although progress has at times been constrained by political, technical, and implementation challenges.

Contributions to policy coherence have primarily been through multilevel institutional collaboration and legal reforms. In a sample of 48 completed GEF-6 and GEF-7 projects reviewed for policy coherence outcomes, 39 included activities designed to contribute to such outcomes3. Of these, 87 percent (34 projects) implemented the planned activities, and 46 percent (18 projects) achieved one or more tangible intersectoral policy coherence outcomes, confirming stakeholder experiences that policy reform processes often take longer to complete than the typical project implementation period.

Projects supported policy coherence in several ways. These included integrating agrobiodiversity and sustainability principles into national development plans, budget programs, and sectoral policies; formalizing transboundary agreements; and operationalizing data-sharing frameworks among ministries to facilitate the development of climate-resilient legislation across sectors. National and local policies were harmonized by strengthening the capacities of local governance structures in areas including participatory forest management, municipal waste management, and urban environmental integration.

Strong ownership among governments and other stakeholders contributed to the effectiveness of policy coherence-focused interventions. This ownership was attributable in part to project alignment with existing priorities and partnerships. In contrast, limited progress was attributed to factors such as limited political support, lack of technical capacity, and insufficient implementation time relative to the duration of political and other institutional processes.

Projects from earlier GEF replenishment periods demonstrate how GEF interventions have contributed to policy coherence. In Morocco, the Energy Efficiency Codes in Residential Buildings and Energy Efficiency Improvement in Commercial and Hospital Buildings in Morocco (GEF ID 2554, UNDP) project approved under GEF-3 played a key role in the development of Energy Efficiency Law No. 47-09, which introduced building codes, mandatory audits, and environmental impact requirements for urban development. It also spurred the launch of a national green cities program. In the Western Balkans, the Protection and Sustainable Use of the Dinaric Karst Aquifer System (GEF ID 3690, UNDP) project established interministerial committees in four countries to harmonize water policies, contributing to the creation of Albania’s Water Resources Management Agency.

While challenges such as staff turnover and funding delays affected progress, GEF-supported tools and approaches helped strengthen national policy coherence. The Forest Conservation and Sustainability in the Heart of the Colombian Amazon (GEF ID 5560, World Bank) project leveraged integrated planning processes to embed biodiversity conservation into municipal, regional, and sectoral programs in postconflict areas. Success was driven by strong government commitment, institutional stability, cross-sectoral champions, and a long implementation period of over 10 years.

Several other examples highlight that GEF projects did not always achieve policy coherence. In Malawi, the Private Public Sector Partnership on Capacity Building for Sustainable Land Management in the Shire River Basin (GEF ID 3376, UNDP) supported policy development across the forestry, charcoal, agriculture, and energy sectors. Conflicting maize subsidies and weak enforcement of the charcoal strategy made sustainable land management economically nonviable for farmers, leading to continued land and forest degradation. Similarly, Uruguay’s mercury management project (GEF ID 4998) contributed to a national ban on mercury-containing medical products and supplied mercury analysis equipment to the Ministry of Public Health, but limited institutional capacity hindered full coordination with the environment ministry in these initiatives.

.jpg)

Many of the environmental challenges the GEF seeks to address are rooted in human behaviors, which can be changed through targeted interventions. While the GEF has historically aimed to influence behavioral drivers of environmental degradation, a 2020 assessment by the Scientific and Technical Advisory Panel found that most projects did not explicitly articulate how they would promote behavior change leading to environmental benefits (Metternicht, Carr, and Stafford Smith 2020). In GEF-8, however, many integrated programs have begun to position behavior change as a key strategy for achieving large-scale environmental impact.

The GEF IEO reviewed 37 completed GEF-6 and GEF-7 projects and 21 ongoing GEF-8 projects that targeted behavior change. Knowledge and skill building in pro-environment practices emerged as the most frequently used approach to behavior change. Across these projects, lack of expertise was identified as the most common barrier. For instance, by providing training to small farmers, the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Globally Important Agro-biodiversity (GEF ID 6943, UNDP) project in Azerbaijan facilitated a switch to native crops in more than triple the number of targeted households, consequently restoring more than 1,000 hectares of degraded land.

More recent projects are increasingly addressing not only technical knowledge gaps but also stakeholder needs and institutional barriers to enable behavior change. While both completed and ongoing projects often aim to motivate behavior change through improved legal frameworks or awareness raising, GEF-8 projects show a greater focus on aligning interventions with stakeholder needs (38 percent versus 14 percent in earlier projects) and strengthening institutional capacities (43 percent versus 24 percent). In Panama, for example, the Strengthening Ecological Connectivity in Natural and Productive Landscapes Between the Amistad and Darien Biomes (GEF ID 11209, UNDP) project aims to curb unsustainable subsistence farming by promoting biodiversity-friendly livelihoods through partnerships with value chain actors, including civil society and financial institutions.

Behavior change indicators have shown positive results. The majority of projects successfully met their behavior change targets, with nearly half also achieving the associated environmental outcomes. In Turkmenistan’s Supporting Climate Resilient Livelihoods in Agricultural Communities in Drought-prone Areas (GEF ID 6960, UNDP) project, for example, efforts to promote climate-resilient agriculture met both behavioral targets, with over 3,000 farmers adopting new practices; and environmental goals, including improved irrigation across 20,000 hectares. Other targeted behavioral changes include practices such as planting native crops, segregating waste, and complying with stricter fishing regulations. Some projects, such as those in the climate change focal area, have promoted the adoption of technologies like LED lighting and renewable energy microgrids; projects in other focal areas aim to reduce environmentally harmful behaviors such as poaching and mercury use. However, fewer than half of the projects include explicit behavior change indicators.

While awareness raising and training were effective in catalyzing initial change, sustaining new behaviors depended heavily on access to capital, perceived cost-benefit advantages, and continued institutional support. In Enhancing Resilience of Agricultural Sector in Georgia (GEF ID 5147, International Fund for Agricultural Development), pilot beneficiaries continued to invest in climate-resilient agricultural measures three years after project closure. In contrast, those trained but without benefiting from material support were less able to implement the full suite of practices, resulting in economic losses that hindered further adoption. Similarly, in the Philippines SLM project (GEF ID 5767), some farmers replicated sustainable practices postproject through continued government support. Others continued to practice conventional farming given its quicker returns and fewer skill requirements—despite the higher risks and lower incomes associated with those methods.

These findings suggest that behavior change is critical to achieving environmental outcomes and requires supportive conditions to endure. These include available capital, institutional support and incentives, and lower costs of adoption to enable scaling beyond initial pilot efforts. Projects that integrate these elements into their design are more likely to produce lasting and replicable environmental benefits.

Sources: GEF Portal and GEF IEO Annual Performance Report (APR) 2026 data set, which includes completed projects for which terminal evaluations were independently validated through June 2025.

Note: Data exclude parent projects, projects with less than $0.5 million of GEF financing, enabling activities with less than $2 million of GEF financing, and projects from the Small Grants Programme. Closed projects refer to all projects closed as of June 30, 2025. The GEF IEO accepts validated ratings from some Agencies; however, their validation cycles may not align with the GEF IEO’s reporting cycle, which can lead to some projects with available terminal evaluations lacking validated ratings within the same reporting period; thus, validated ratings here are from the APR data set only.