Key sources of evidence include the evaluations on drylands countries, climate information and early warning systems (CIEWS), and the Least Developed Countries Fund/Special Climate Change Fund (LDCF/SCCF) annual evaluation reports for 2023–25 (GEF IEO 2024f, 2024e, 2025f, 2025g, forthcoming-m).

The LDCF/SCCF portfolio has transitioned from focusing on targeted vulnerability reduction to embracing integrated, system-level adaptation. Interventions under GEF-5 and earlier periods concentrated on reducing vulnerability and increasing adaptive capacity. Since GEF-6, programming has shifted toward addressing the systemic drivers of climate risk, aligning more closely with national planning and institutional frameworks. GEF-7 emphasized innovation and private sector engagement, while GEF-8 introduced transformational adaptation and systems resilience as core concepts (GEF 2022b).

Recent projects have adopted a catalytic approach, leveraging external finance and partnerships. Whereas earlier efforts were primarily pilot initiatives, GEF-7 and GEF-8 projects increasingly aim to mobilize additional investments from the Green Climate Fund and other multilateral or bilateral sources. This approach aligns with the strategic focus on scaling up finance and delivering broader impacts.

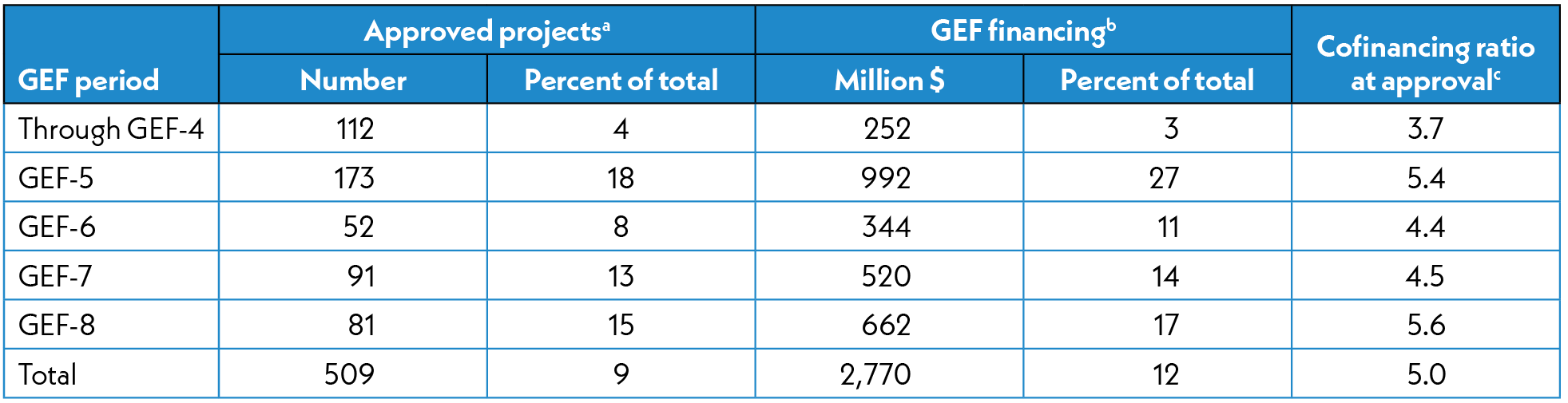

Data on the portfolio on climate change adaptation show a decline in financing between GEF-5 and GEF-6, followed by a partial recovery from GEF-7. The number of projects approved has declined, while the ratio of expected cofinancing has remained stable (table 5.2). UNDP has historically played a leading role in the adaptation portfolio, but in GEF-8, international financial institutions—particularly the World Bank—have taken on a larger share of programming. Africa has received by far the largest share of financing, which has further increased under GEF-8.

Sources: GEF Portal as of June 30, 2025. See table D.26.

a. Includes multifocal area projects; excludes dropped and canceled projects without a first disbursement.

b. Includes Agency fees and project preparation grant funding and fees.

c. Excludes multitrust fund and multifocal area projects; GEF financing excludes Agency fees and project preparation grant funding and fees.

The adaptation portfolio has advanced beyond conventional classification frameworks, evolving into more sophisticated and integrated programming. Interventions now span five main thematic areas and incorporate a combination of hard infrastructure, soft measures, capacity building, technology transfer, and ecosystem-based approaches to comprehensively address systemic climate vulnerabilities. These climate change adaptation efforts can be broadly categorized into five main groups:

GEF adaptation interventions under the LDCF/SCCF remain aligned with guidance from the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Conference of the Parties (COP) and the objectives of the Paris Agreement. As financial mechanisms of these agreements, the LDCF and SCCF have responded to evolving COP priorities, particularly those highlighted at COP27, COP28, and COP29. COP decisions emphasized improving access to finance for least developed countries (LDCs) and small island developing states (SIDS), supporting gender-responsive and locally led adaptation, advancing national adaptation plans, and enhancing coherence among climate funds. In response, GEF-8 programming has prioritized country ownership, institutional capacity building, and regional collaboration through multicountry initiatives and workshops. At COP29, parties requested the GEF to strengthen coherence across funds, streamline access for eligible countries, and deepen engagement with national and regional institutions in underserved regions. While approaches have evolved, the climate change adaptation portfolio continues to reflect the priorities and guidance set forth by the COP and the Paris Agreement, and the LDCF/SCCF also have aimed to prioritize the needs of individual countries and communities.

Over time, GEF adaptation projects have evolved to include both upstream investments in climate data and services and downstream actions that enhance preparedness and response. The IEO’s CIEWS evaluation (GEF IEO 2025f) found that most interventions have been implemented at the local level (39 percent), focusing on livelihood resilience, ecosystem-based adaptation, and early warning systems. National-level interventions (33 percent) have strengthened climate governance and policy integration. State and regional-level efforts (20 percent) have enabled transboundary cooperation, promoting coordinated climate risk management. Multicountry interventions (7 percent) have supported regional collaboration on shared climate challenges such as desertification and extreme weather events.

.JPG)

Data available for completed projects show different trends in outcome achievement and sustainability. The percentage of completed projects assessed as moderately satisfactory or higher for outcome achievement increased from 81 percent under GEF-1 to GEF-4 cumulatively to 82 percent under GEF-5 and 90 percent under GEF-6 (figure 5.2)—although in the latter period, the number of projects observed is smaller. The percentage of projects assessed at completion as moderately likely or above for sustainability dropped from 71 percent under GEF-1 to GEF-4 cumulatively to 53 percent under GEF-5 and increased only slightly to 56 percent under GEF-6—again, with a smaller number of observations. The quality of implementation and execution and M&E design and implementation show improving rating trends. Box 5.3 presents examples of more and less effective projects and selected explanatory factors.

Sources: GEF IEO Annual Performance Report 2026 data set, which includes completed projects for which performance ratings were independently validated through June 2025. See table D.19, table D.20, table D. 21, table D.22, table D.23, and table D.24

Note: M&E = monitoring and evaluation. The numbers of projects for which validated outcome ratings are available are in parentheses. The cumulative figure for all periods includes GEF-7, which is not shown separately due to the limited number of observations.

The CIEWS evaluation found that LDCF/SCCF interventions have significantly contributed to improving climate information systems, enhancing institutional capacity, and integrating adaptation measures into national policies. Investments in modernized meteorological infrastructure and expanded automated weather stations have contributed to a 30 to 50 percent increase in forecasting accuracy in target regions, enabling earlier disaster response. Early warning coverage reached over 60 percent of vulnerable populations in LDCs, correlating with reduced fatalities during cyclones and floods. In a UNDP-implemented project on strengthening CIEWS in Cambodia (GEF ID 5318), 15 automated weather stations were installed, improving flood forecasting accuracy by 50 percent and reaching 1.2 million people. Regional projects, such as Climate Change Adaptation in the Eastern Caribbean Fisheries Sector (GEF ID 5667, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations [FAO], improved storm surge alerts, contributing to a 60 percent reduction in disaster-related fatalities.

The key achievements in agricultural adaptation included increased adoption of drought-tolerant crops and expanded extension services, which improved food security in vulnerable regions. Reduced postharvest losses were also noted through storage innovations and enhanced market access, though scaling pest surveillance systems remained challenging. Several country examples illustrate these impacts. In Niger and Burkina Faso, projects led by FAO on farmer field schools trained over 15,000 farmers in drought-tolerant techniques, boosting yields by 25 to 40 percent. In Malawi’s Climate Proofing Local Development Gains in Rural and Urban Areas of Machinga and Mangochi Districts (GEF ID 4797, UNDP), postharvest innovations such as improved grain storage systems reduced losses by 30 percent.

Integrated water resource management dominated interventions, emphasizing rainwater harvesting, drip irrigation, and hydrological modeling. The 2023 and 2025 LDCF/SCCF annual evaluation reports underscore improved water access in drought-prone regions (GEF IEO 2024c, forthcoming-q), with projects in Sub-Saharan Africa and SIDS enhancing agricultural yields through efficient irrigation. Policy reforms enabled equitable water allocation, reducing conflicts in transboundary basins. However, maintenance of water infrastructure and long-term financing gaps were recurring challenges. In Strengthening Capacities of Rural Aqueduct Associations to Address Climate Change Risks in Water Stressed Communities of Northern Costa Rica (GEF ID 6945, UNDP), drip irrigation increased water efficiency by 40 percent. Uganda’s Building Resilience to Climate Change in the Water and Sanitation Sector (GEF ID 5204, African Development Bank) project introduced gender-inclusive sanitation infrastructure, boosting girls’ school enrollment by 20 percent, but faced procurement delays that slowed implementation.

The integration of climate change adaptation into broader development planning has shown mixed results. While some projects have successfully mainstreamed climate resilience, others have remained confined to their respective sectors. Despite this inconsistency, a key strength of GEF adaptation interventions has been their catalytic effect. Projects have effectively mobilized cofinancing and fostered multistakeholder partnerships, extending their impacts beyond initial funding cycles. The LDCF/SCCF annual evaluation reports for 2023 and 2025 highlight that adaptation projects have often laid the groundwork for scaling up investments from other climate funds, national governments, and the private sector, enhancing their overall effectiveness.

Enhancing Sustainability and Climate Resilience of Forest and Agricultural Landscape and Community Livelihoods in Bhutan (GEF ID 9199, United Nations Development Programme [UNDP])

Building Shoreline Resilience of Timor-Leste to Protect Local Communities and Their Livelihoods (GEF ID 5671, UNDP)

Successful innovations within the LDCF/SCCF portfolios have emerged mainly in information-sharing platforms and data usage. Risk and vulnerability platforms have improved links between beneficiaries and policymakers, with the SCCF portfolio for non-LDCs showing higher innovation rates. Notable examples include the Southeastern Europe and Caucasus Catastrophe Risk Insurance Facility (GEF ID 4515, World Bank) and Costa Rica’s rural aqueduct associations project (GEF ID 6945, UNDP), which successfully implemented low-maintenance sensor systems for water monitoring. Additionally, the integration of social networks and messaging platforms has enhanced communication with local communities.

A major gap remains between innovative planning and implementation. While 22 percent of evaluated CIEWS projects included innovative features at the design stage, only 5 percent successfully implemented them by project completion. Innovation also varies by sector. Remote sensing and mobile technologies show promise in climate-smart agriculture, early warning systems, and ecosystem-based adaptation, but challenges to scaling persist. These include weak private sector partnerships, limited technical capacity, and inadequate funding. The 2025 LDCF/SCCF annual evaluation report notes that pilots often lack scaling pathways, and coordination with research institutions remains underdeveloped.

The sustainability of GEF-funded adaptation interventions has remained a challenge. The LDCF/SCCF annual evaluation reports for 2023, 2024, and 2025 highlight that sustainability is particularly fragile in LDCs and SIDS because of financial constraints, institutional capacity gaps, and sociopolitical instability.

A persistent challenge has been the lack of long-term financial mechanisms to sustain project benefits beyond initial funding. Many climate change adaptation interventions rely heavily on donor support, and while some projects have successfully leveraged cofinancing, securing ongoing resources for maintenance, capacity building, and scaling remains difficult. Furthermore, institutional ownership and policy integration have been inconsistent across projects. Another key factor affecting sustainability is the implementation of exit strategies and follow-up commitments. Projects that incorporated clear transition plans, including capacity-building efforts, private sector engagement, and local community involvement, had better sustainability prospects.

Sources: GEF Portal and GEF IEO Annual Performance Report (APR) 2026 data set, which includes completed projects for which terminal evaluations were independently validated through June 2025.

Note: Data exclude parent projects, projects with less than $0.5 million of GEF financing, enabling activities with less than $2 million of GEF financing, and projects from the Small Grants Programme. Closed projects refer to all projects closed as of June 30, 2025. The GEF IEO accepts validated ratings from some Agencies; however, their validation cycles may not align with the GEF IEO’s reporting cycle, which can lead to some projects with available terminal evaluations lacking validated ratings within the same reporting period; thus, validated ratings here are from the APR data set only.