This section draws from the recent IEO evaluation of the chemicals and waste focal area (GEF IEO forthcoming-h).

The GEF has made progress in addressing many relevant chemicals and waste–related issues. For example, the GEF supported countries with significant industries in textiles, dental amalgam, and skin-lightening products, aligning with key sectoral priorities. However, gaps remain in addressing other critical areas, in part due to limited demand from the countries. For instance, despite the importance of e-waste recycling in Uruguay, the country has not proposed to the GEF a project focused on safe e-waste dismantling.

The GEF has moved from focusing on individual chemicals, such as PCBs, pesticides, and mercury, toward a broader, sectorwide approach. The GEF chemicals and waste portfolio shows a clear shift toward integrated programming, as seen by the increasing allocation of funding to programs and child projects from GEF-5 to GEF-8. The GEF-5 and GEF-6 strategies focused on a chemical-by-chemical approach. With the programmatic strategies of GEF-7 and GEF-8, the GEF shifted from a single-chemical focus, such as persistent organic pollutants (POPs) or mercury, to an integrated, sectoral approach that addresses chemicals throughout their entire life cycle and supply chains.

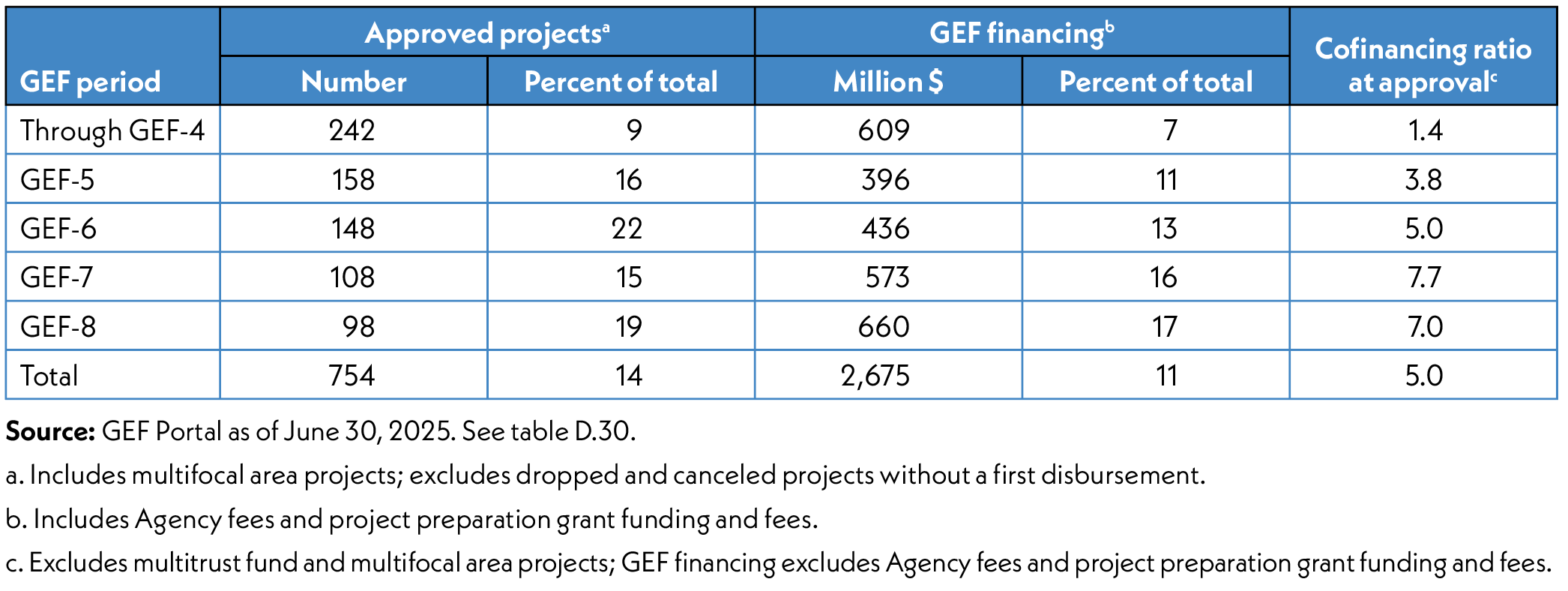

Table 5.6 shows the evolution of projects and funds approved for the chemicals and waste focal area. It highlights the decline in the number of projects approved from GEF-5, concurrent with the increase in financing approved and the increase in expected cofinancing at project approval. At a more disaggregated level, the share of funding to the World Bank declined since GEF-5; the main lead Agencies in terms of financing are now UNDP, UNEP, and the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO). The Africa region has the highest share of financing, closely followed by Latin America and the Caribbean and Asia.

Capacity-building and environment improvement investments have been the main areas of intervention in a portfolio of 439 closed and ongoing projects. In the closed projects, the most frequently reported interventions are capacity building, environmental improvement investments in machinery or removal of contaminated soil, and knowledge management. In contrast, the portfolio of ongoing projects shows considerable increases in interventions aimed at achieving socioeconomic results; implementing legal, policy, and regulatory measures; and conducting environmental monitoring.

The GEF plays an important role in supporting implementation of the Stockholm and Minamata Conventions, with recipient countries generally recognizing its alignment with convention guidance.3 The GEF’s responsiveness to Stockholm Convention COP guidance received a strong average rating of 4.3 out of 5, according to a survey of recipient countries conducted by the Stockholm Convention (UNEP 2024a). Challenges persist, however, in low-income economies, because of the high costs of alternatives, limited access to resources, funding delays, and narrow project scopes. In addition, the GEF has supported 59 enabling activities related to the Stockholm Convention in GEF-5, of which 56 aimed to update existing national implementation plans in response to added POPs. However, only about 30 percent of countries submitted updated national implementation plans to the Stockholm Convention Secretariat within the required two-year time frame, highlighting significant delays in national delivery and compliance.

The GEF’s efforts to address chemical pollution are relevant both to countries and to the objectives of the Stockholm Convention, particularly in tackling major challenges related to PCBs, pesticides, and DDT. However, while the GEF has supported countries with significant stockpiles, its reach has been limited. For example, of the 21 countries identified as having the largest PCB stockpiles, only one—Antigua and Barbuda—benefited from targeted GEF interventions in GEF-5 and GEF-6. Similarly, among the 11 countries with the largest DDT stockpiles, only three received GEF support, leaving the needs of several countries unaddressed.

The shift from a chemical-by-chemical to a sector-based approach in GEF-7 has enhanced integrated chemical management across industries but risks neglecting legacy chemicals. An integrated approach to programming is essential for effective chemicals and waste management, particularly in the garment and food packaging sectors, where chemicals are used extensively throughout the supply chain. The GEF’s focus on addressing chemicals at every stage is appropriate to prevent the proliferation of harmful substances and ensure sustainable practices across industries. While this shift presents substantial advantages, it has also led to a reduced focus on legacy chemicals in recent projects. Despite the decrease in single-chemical initiatives, many countries still urgently need assistance in safely managing and disposing of PCBs to meet the 2028 Stockholm Convention deadline and help with other legacy chemicals to combat pollution and enhance public health. Meanwhile, and in response to COP-10, the GEF acted on the PCB deadline by approving a global PCB management program at its December 2024 Council meeting. While the transition to a sectorwide approach presents risks of gaps in targeted chemical management support, the GEF is addressing this challenge through complementary measures to ensure support where it is most needed.

Chemicals and waste projects have shown positive performance overall. Through GEF-4, 83 percent of the completed projects were rated moderately satisfactory or higher for outcome achievements, a percentage that remained almost unchanged under GEF-5 (figure 5.6). A further increase is visible under GEF-6 but is based on a smaller number of observed projects. Similar improved trends are visible for quality of implementation and execution and M&E design and implementation.

Source: GEF IEO Annual Performance Report 2026 data set, which includes completed projects for which performance ratings were independently validated through June 2025. See table D.19, table D.20, table D. 21, table D.22, table D.23, and table D.24.

Note: M&E = monitoring and evaluation. The numbers of projects for which validated outcome ratings are available are in parentheses. The cumulative figure for all periods includes GEF-7, which is not shown separately due to the limited number of observations.

The effectiveness of GEF chemicals and waste projects has varied based on how effectively they engaged with national legislation—both by aligning with existing laws and by supporting efforts to improve them. Strong legislative frameworks have been instrumental in the success of chemicals and waste management projects. However, enforcement and outcomes have shown significant variability across countries. Laws such as extended producer responsibility play a key role in securing private sector engagement, while setting adequate tariffs for waste collection companies helps maintain consistent service delivery. Legislation has played a crucial role in scaling up pollution prevention in some countries. Additionally, formalizing the role of informal waste pickers or banning their involvement in e-waste collection reduced health risks and environmental harm. However, inconsistent enforcement of these legal measures in some countries has posed challenges, ultimately affecting the effectiveness and sustainability of project outcomes.

In the Arab Republic of Egypt, the Protect Human Health and the Environment from Unintentional Releases of POPs (GEF ID 4392, UNDP) project met its e-waste collection targets through a pioneering initiative led by multinational mobile phone companies, with an online platform for household e-waste collection; it laid the groundwork for national waste electrical and electronic equipment facilities. Legislation banning informal e-waste collection and dismantling addressed pollution risks reduced unintentional POPs emissions and enabled the formalization of the sector through licensed waste managers. This initiative fostered safer, more sustainable e-waste management and created formal employment opportunities.

Technological innovations—while not always new globally—can be transformational within the countries where they are implemented, delivering significant environmental benefits. In Viet Nam (GEF ID 9379, UNDP), green chemistry approaches in the metal plating industry have reduced the use and release of hazardous substances. In Trinidad and Tobago (GEF ID 5558, UNIDO) and Senegal (GEF ID 4888, UNIDO), the deployment of autoclaves to replace carbon dioxide–emitting incinerators and the introduction of laboratory equipment have improved the safe treatment and monitoring of hazardous waste. Safer pesticides use in Trinidad and Tobago (GEF ID 5407, FAO) and expanded recycling infrastructure have further advanced chemical safety and supported circular economy practices. Additionally, the replacement of dental amalgam (GEF ID 10936) in Senegal, Uruguay, and Thailand has reduced mercury pollution and health risks. These interventions also contribute to global efforts toward safer, more sustainable chemical management along supply chains.

However, smaller firms and chemical suppliers are often overlooked in broader interventions. In developing countries, the textile and apparel industry is predominantly made up of small enterprises and microenterprises, facing challenges in adopting sustainable practices due to limited financial resources and technical expertise. For industrywide transitions to eco-friendly practices, targeted support for smaller players is essential, as supported by the International Finance Corporation/GEF Decarbonization of Textile, Apparel & Footwear Suppliers (D-TAFS) Fund (GEF ID 11326, World Bank), for example. Addressing high-cost barriers and involving suppliers more actively could have enabled smaller firms to better manage chemicals and adopt sustainable practices across the supply chain.

Efforts to prevent and remediate chemical pollution in GEF projects are likely to generate socioeconomic and health co-benefits. However, these benefits remain underappreciated due to the absence of systematic tracking. Quantifying health co-benefits is challenging due to the lack of standardized indicators and the long-term nature of health impacts, often extending beyond project timelines. A case in point is Indonesia’s project Reducing Environmental and Health Risks to Vulnerable Communities from Lead Contamination from Lead Paint and Recycling of Used Lead Acid Batteries (GEF ID 5701, UNDP), which successfully remediated a contaminated site where local communities had been dismantling e-waste and batteries, unaware of the associated health risks. Despite these significant interventions, no formal assessment of health outcomes was conducted, leaving potential long-term benefits undocumented.

The GEF’s focus on the food and beverage supply chain, particularly at the end-of-life stage, highlights the sustainability of prevention over remediation.4 The GEF’s progression toward upstream prevention represents a significant evolution from GEF-5 to GEF-8. Allowing plastics and packaging waste to accumulate in landfills leads to carbon dioxide and methane emissions, costly geoengineering, and the risk of toxic leakage. The GEF’s preventive approach, including recycling, composting, and waste reduction, has proven to be sustainable when the introduction of technology is accompanied by technical capacity and financing—for example, accompanying the adoption of new non-incineration technologies (such as autoclaves) with efforts to strengthen the national regulatory environment and build capacities to use the new technologies. However, in countries with insufficient training, limited technical expertise, constrained maintenance budgets, and supply chain challenges, imported machinery—such as autoclaves and laboratory equipment—has often remained underused. Additionally, integrating informal waste pickers into formal waste management systems enhances both environmental outcomes and social equity, creating a more comprehensive and inclusive strategy for waste management.

The Implementation of Eco-Industrial Park Initiative for Sustainable Industrial Zones in Viet Nam (GEF ID 4766, UNIDO) exemplified transformational change by integrating environmental, economic, and social improvements across industrial zones. The project introduced resource-efficient, low-emission practices in 676 small and medium enterprises and established 10 industrial symbiosis schemes across three pilot zones. In Ninh Binh, for instance, a gas company captured byproducts from a fertilizer factory and sold them to a beverage company, demonstrating practical and profitable resource sharing. These interventions contributed to an estimated annual reduction of 2.9 million metric tons of carbon dioxide emissions. Crucially, the adoption of Decree 82 enabled the national scaling of the eco-industrial park model by providing a formal regulatory framework and institutional backing. Sustained collaboration among government ministries, the private sector, and local communities further reinforced trust, policy alignment, and social equity—key ingredients for durable environmental impact. Transformational outcomes in Viet Nam were enabled by strong internal design features, including a barrier analysis that addressed low awareness, weak enforcement, and limited recycling confidence. Cross-sectoral coordination through a high-level steering committee ensured government ownership, while capacity-building activities—training, study tours, and joint planning—supported adaptive learning and long-term change.

Private sector involvement has been vital for sustainability. The GEF’s market-oriented strategies, combined with local business participation and technology transfer, have laid the groundwork for transformational change. In some instances, sustainability was supported through a combination of GEF financing, government legislation or subsidies, certification schemes, or partnerships with international firms. For instance, in Viet Nam, the introduction of eco-industrial park legislation facilitated the nationwide adoption of a resource-sharing model, which encourages interconnected industries to optimize resource efficiency by sharing resources, implementing recycling systems, and collectively reducing carbon dioxide emissions (box 5.7).