This section focuses on the main components of the GEF partnership—specifically, the countries in which GEF initiatives are undertaken, the GEF Agencies that undertake these initiatives, the STAP, and civil society.

Guided by its Country Engagement Strategy (CES), the GEF supports countries in aligning global environmental commitments with national priorities through country-driven programming and multistakeholder dialogue. The GEF Agencies—including United Nations (UN) entities, multilateral development banks, and international nongovernmental organizations (INGOs)—translate these priorities into actionable projects and programs. The STAP ensures that scientific rigor and innovative approaches inform GEF investments; while civil society completes the partnership circle by fostering community participation, inclusion, accountability, and local legitimacy.

The GEF brings together both donor and recipient countries through a council structure that reflects a broad and inclusive set of constituencies, ensuring diverse perspectives in decision-making. Each country appoints a GEF operational focal point (OFP) to coordinate national engagement, identify priorities, and align GEF support with national strategies.

The diversity of partners and partnerships supports country priorities through both project-based operations and dedicated mechanisms that strengthen country ownership and alignment with global environmental priorities. A key mechanism is the CES, launched in October 2022 as an evolution of the earlier Country Support Program (CSP). The CES is an important mechanism aimed at helping recipient countries make informed, impactful decisions on the use of GEF resources while enhancing sustainability, coherence with national policies, and visibility of GEF support. By consolidating various country engagement activities into a unified framework, the CES seeks to enhance country ownership, improve alignment with GEF and national priorities, raise the GEF’s visibility, strengthen policy coherence for environmental benefits, and promote coordination with other environmental funding sources. This section focuses on recent adjustments under the CES, including its expanded scope, structure, and budget, and highlights how these changes aim to provide deeper, more integrated support to countries.

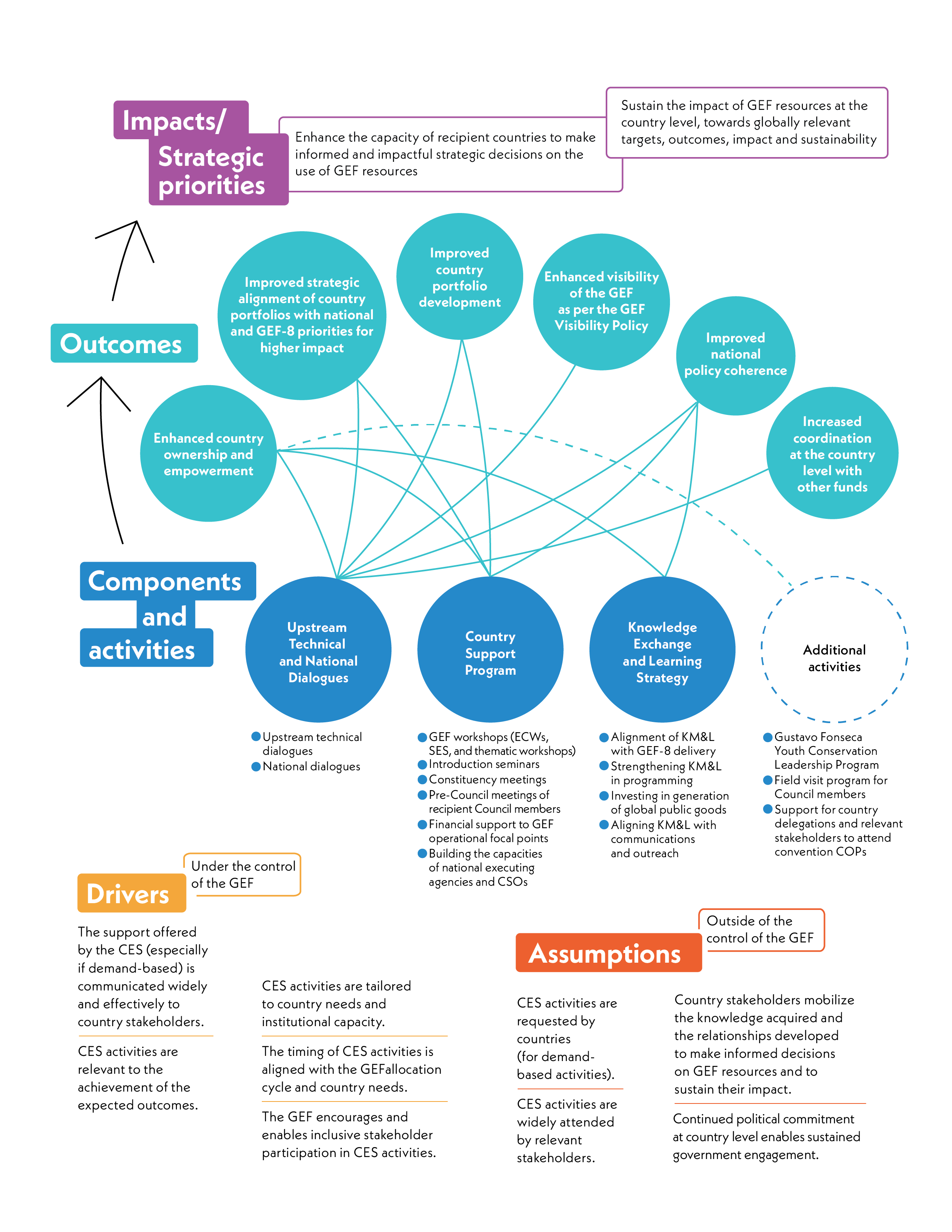

In the absence of a theory of change for the CES, figure 10.1 provides a visual summary of the CES intervention logic developed by the IEO and seeks to identify the underlying drivers and assumptions that must hold for CES components to influence expected outcomes and impacts.1

The CES is structured around four key components: upstream technical and national dialogues; the CSP, including ongoing and new activities such as financial support to GEF OFPs; the Knowledge Management and Learning (KM&L) Strategy; and a range of supplementary initiatives, including the Gustavo Fonseca Youth Conservation Leadership Program, Council member field visits, and support for international convention participation.

The total CES budget for GEF-8 rose by 44 percent from the GEF-7 CSP level. With an allocation of $40.2 million, up from $21.0 million in GEF-7 and representing 0.8 percent of the total GEF-8 budget, the CES budget’s increase over that of the GEF-7 CSP reflected an ambition to provide deeper, more integrated support to countries. The budget included $27.0 million for core CES activities and $13.2 million for additional programs. In contrast, the budget for legacy CSP activities declined by 14 percent. National dialogues and constituency meetings accounted for the largest share of the CES budget.

The CES’s principal value lies in its attempt to centralize and coordinate country engagement under a single strategic umbrella. While pre-GEF-8 activities were scattered across multiple programs, the CES now integrates CSP efforts with new proactive engagement activities and the KM&L Strategy. However, actual implementation of these new elements has been slower than anticipated, and their full potential has yet to be realized.

By June 30, 2025, CES implementation remained uneven, with significant variations in performance across activities, countries, and regions. As of end June 2025, 75 CES activities had been conducted, a reduction from the 103 activities implemented at the same point in GEF-7. This shortfall in delivery is particularly concerning given the expanded mandate and budget of the CES. Among the activities, 29 national dialogues had been held, putting the program on track to meet its GEF-8 target of 50—although many occurred later than optimal, limiting their influence on programming. Survey data further indicate mixed perceptions of timeliness, with just over half (56 percent) of respondents rating CES activities as timely to support GEF-8 programming. While GEF-8 integrated program rollout workshops were timely, national dialogues were less effectively leveraged.

Source: GEF IEO 2025d. Note: CES = Country Engagement Strategy; COP = conference of the parties; CSO = civil society organization; ECW = expanded constituency workshop; KM&L = knowledge management and learning; SES = sector engagement strategy.

Expanded constituency workshops also fell short, with only 10 out of a planned 22 held by June 2025, because priority was given to GEF-8 integrated program rollout workshops. Other activities, such as the Stakeholder Empowerment Series and building execution capacity of stakeholders, had not begun implementation. In contrast, introduction seminars were nearly on track, with three of four planned sessions completed, benefiting from a virtual delivery format. The Gustavo Fonseca Youth Conservation Leadership Program supported 187 participants, and 39 individuals received support to attend conferences of the parties (COPs) under the relevant environmental conventions. Of a potential total of 76 constituency meetings, 20 were held; and only one pre-Council meeting had taken place. The uneven implementation of these demand-based activities highlighted a systemic issue: OFPs, who are responsible for initiating many CES engagements, often lacked the necessary institutional support, information, or time to proactively engage with the GEF Secretariat.

Performance data reveal disparities in budget execution across the CES. As of end June 2025, 47 percent of the CES’s $40.2 million budget had been committed or disbursed, with significant variation across activities. For example, 90 percent of the budget for constituency meetings was used, while less than half was disbursed for national dialogues, financial support for OFPs, and knowledge exchange and learning; this last accounted for only 3 percent of the budgeted amount. Delays in disbursing funds for OFP support were largely due to World Bank regulations that prohibit direct transfers to individuals. This challenge was addressed through ancillary agreements, first piloted under the Gustavo Fonseca Youth Conservation Leadership Program, which has successfully disbursed 72 percent of its budget by providing fellowships to 187 participants.

Regional differences in CES activity are pronounced. The Africa region, with the largest number of least developed countries (LDCs), had the highest participation rate, including 18 of the 29 national dialogues. Countries in Asia and the Pacific showed more balance between national dialogues and constituency meetings, while Latin America and the Caribbean participated in a broader range of newer activities, including the youth program and COP support. In contrast, Eastern Europe and Central Asia—a region with relatively higher institutional capacity—had minimal engagement and no national dialogues during the period reviewed.

Participation in CES activities has been strong among LDCs, but more limited for small island developing states (SIDS), revealing important geographic disparities. LDCs accounted for 44 percent of national dialogues (13 of 29) and participated in more than half of CES activities overall. This high engagement rate reflects both strong need and successful outreach. SIDS, by contrast, were comparatively less represented, participating in only 14 percent of national dialogues and 33 percent of all CES activities. Their participation was somewhat higher in virtual events, such as introduction seminars, due to fewer logistical barriers. Still, the lack of activities explicitly tailored to the unique needs of SIDS remains a missed opportunity.

.jpg)

The CES has made meaningful contributions to enhancing country ownership and strengthening country portfolio development, particularly in cases where countries engaged in a wide range of its activities. In the Philippines, for instance, the CES contributed significantly to portfolio development. The national dialogue was carefully designed around project concept presentations and stakeholder feedback. It was preceded by a GEF-8 regional workshop and followed by bilateral meetings with GEF Secretariat staff; these allowed the country to refine its portfolio. Suriname, which had not held a national dialogue since 2009, used its 2024 event to launch a more inclusive and participatory approach to portfolio development for GEF-9. In Honduras, the CES helped raise awareness of opportunities beyond the System for Transparent Allocation of Resources (STAR) allocation, including the Global Biodiversity Framework Fund (GBFF) and the Capacity-building Initiative for Transparency, which translated into the development of proposals under multiple funding windows. Such examples underscore the potential of CES activities to strengthen strategic planning and stakeholder engagement at the national level.

The CES contributed to improved alignment between country portfolios and both national development plans and GEF programming objectives. In Uganda, for example, the CES accomplished this alignment by creating space during the programming phase to assess how proposed projects relate to national development objectives and to identify new project ideas aligned with these priorities.

Participation in CES events increased awareness of GEF-8 focal area strategies, priorities, funding windows, and programming expectations. For example, in the Philippines, as a follow-up to the national dialogue, the GEF Secretariat staff provided detailed feedback to the OFP team on the proposed portfolio. This feedback addressed the potential eligibility of each project and the key elements that needed to be considered to better align them with an integrated programming focus.

The CES has played an indirect but supportive role in advancing policy coherence within GEF recipient countries. As emphasized in the GEF’s strategic roadmap for enhancing policy coherence (GEF 2023), this objective is embedded within the CES framework. Through interviews and field observations, it is evident that CES activities contribute to policy coherence primarily by fostering cross-sectoral engagement. For instance, CES initiatives have encouraged OFPs to include ministries of finance and planning in national dialogues and to establish interministerial GEF national steering committees. Additionally, expanded constituency workshops prompt country delegations to collaborate with diverse sectoral agencies during the preparation of integrated program child projects. These efforts have reportedly improved interministerial communication and coordination. However, their influence on formal policy alignment or long-term reform remains difficult to assess, given the limited systems in place to track such outcomes. Overall, the CES is currently better positioned as a mechanism for enabling dialogue and coordination than as a direct driver of sustained policy reform.

In terms of coordination with other multilateral climate funds, the CES had limited traction but demonstrated potential. The most notable examples came from Uganda and Rwanda, where joint programming consultations with the Green Climate Fund (GCF) were held in conjunction with CES national dialogues. These engagements led to country-driven discussions on aligning GEF and GCF investments and, in Uganda’s case, influenced the reorganization of a national climate finance unit.

The CES contributed to raising the visibility of the GEF within countries, although results varied. In countries such as Lesotho and Suriname, CES activities were instrumental in raising awareness of the GEF among national stakeholders, some of whom had limited prior exposure to its role. In Lesotho, the national dialogue directly led to increased interest among CSOs in the Small Grants Programme. However, beyond event participation, visibility gains were often limited and did not consistently translate into broader recognition of the GEF’s role among communities or implementing partners. In some cases, the visibility of GEF-funded projects on the ground can be overshadowed by the presence of lead Agencies such as the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) or the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). These examples highlight the potential of the CES to strengthen GEF visibility, while pointing to the need for more targeted efforts across different scales.

In terms of inclusiveness, the CES was widely perceived as an improvement over earlier frameworks. Introduction seminars reached an average of 910 participants under CES—compared to only 80 in GEF-7—primarily due to the adoption of virtual formats. The CES was successful in reaching a wide array of stakeholders, including government agencies, CSOs, academics, and the private sector. LDCs participated in more than half of all CES activities and hosted 13 of the 29 national dialogues. SIDS, while well represented in virtual seminars and GEF workshops, were notably underrepresented in national dialogues, with only four held across SIDS. This imbalance highlighted the need for more tailored approaches to ensure that CES activities are accessible and relevant to smaller and more vulnerable countries.

Structural challenges such as limited OFP capacity hindered the uptake of activities. In many countries, CES-supported participation was largely event based and short term. Limited OFP capacity often hindered the uptake of CES activities. Thailand was a notable exception in this regard; its strong OFP organizational capacity enabled early national dialogue and follow‑through on proposals. By the midpoint of GEF‑8, several planned activities—such as direct financial support to OFPs and capacity building for broader stakeholder engagement—had yet to be launched. Only a few countries experienced multiple or sustained engagements, and opportunities to create synergies across activities were frequently missed, reducing cumulative impact and momentum.

Ownership and engagement remain uneven. Sustainability of engagement was weak, with minimal follow-up mechanisms and delays in financial support undermining long‑term effectiveness. Stakeholders outside central government rarely remained involved beyond initial meetings due to unclear roles, insufficient follow-up, and limited capacity. OFPs, although central to continuous engagement, often operate with staffing shortages and weak institutional mandates. Additionally, the absence of a central management system, a clearly articulated strategy design, and measurable indicators further limited accountability and hindered assessment of CES outcomes. The recent introduction of direct OFP support through ancillary agreements is a positive step forward, but it came too late in the replenishment period to influence early programming.

Delayed timing of national dialogues reduces strategic effectiveness. Many national dialogues are held too late in the GEF replenishment cycle, reducing their ability to influence programming decisions. Survey results show that only 56 percent of respondents felt that CES activities were timely in supporting GEF-8 programming in their country, indicating that many activities were not optimally scheduled to meet national needs. In Lesotho, for example, the national dialogue took place more than a year into the GEF-8 period, limiting its ability to influence the use of STAR allocations and align project proposals with evolving GEF priorities. Stakeholders emphasized the importance of convening national dialogues earlier in the replenishment period to enhance their relevance and impact on programming decisions.

Operational-level coordination with other multilateral funds is limited. Despite promising coordination pilots in Rwanda and Uganda in partnership with the Taskforce on Access to Climate Finance, broader operational collaboration between the GEF and other multilateral climate and environment funds remains limited. The GEF, the GCF, the Adaptation Fund, and the Climate Investment Funds did issue a joint declaration in 2023 committing to stronger cooperation, including on capacity building, but this vision has yet to be operationalized at scale through the CES and other processes, limiting opportunities for synergistic programming and resource mobilization. In GEF-8, subregional programming workshops in the Pacific, Indian, and Atlantic Oceans were organized under the LDCF/SCCF with participation from the GCF, enabling countries to explore potential synergies; their contribution to sustained coordination will depend on whether follow-up actions translate into tangible outcomes.

To improve effectiveness under GEF-9, the CES must reinforce both its strategic vision and operational execution. Establishing a clear theory of change, accompanied by SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, time-bound) indicators and a robust monitoring system, is essential to guide implementation and assess results. Strengthened leadership and coordination across the GEF Secretariat are necessary to reduce fragmentation and improve responsiveness. A more differentiated approach—tailored to the diverse capacities and needs of countries, particularly LDCs and SIDS—should underpin future programming. Deeper and more systematic engagement of OFPs, civil society, Indigenous Peoples, youth, and the private sector is needed to broaden ownership and ensure inclusivity. Finally, closer collaboration with other multilateral climate funds would support alignment, reduce duplication, and amplify impact at the country level. While the CES has laid a strong foundation for country-driven engagement, its success in GEF-9 will depend on more coherent, sustained, and adaptive delivery.

The strength of the GEF partnership lies in its broad and diverse network of 18 accredited Agencies. These include UN bodies, multilateral development banks, and INGOs. This structure offers countries a wide range of implementation partners with complementary strengths. The UN entities provide technical expertise and alignment with global conventions; the multilateral development banks bring financial scale, policy influence, and access to high-level government stakeholders; and the INGOs contribute to innovation, inclusiveness, and strong local engagement. The GEF Agencies support countries in designing and implementing GEF-financed projects. Over 180 countries have benefited from GEF funding, with the GEF serving as the financial mechanism for key multilateral environmental agreements.

Agency relationships are integral to the GEF’s operational systems, because GEF Agencies are responsible for translating GEF policies into action through project design, implementation, and oversight. The Agencies operate within their own institutional frameworks, but must meet GEF accreditation standards and comply with key policies on safeguards, gender equality, and stakeholder engagement. They manage financial flows, procurement, risk, and results monitoring, serving as the conduit between country-level execution and GEF-wide operational requirements.

A growing number of GEF Agencies are assuming dual roles in both project implementation and execution. While the GEF defines these as distinct functions that should remain separate, flexibility is permitted in specific cases where a dual role is justified (GEF 2012a, 2019, 2025). Since GEF-5, projects involving a GEF Agency serving as both implementing and executing agency have accounted for 9 percent of the overall portfolio (figure 10.2a). The share of such projects rose from 5 percent of projects and 4 percent of GEF financing in GEF-5 to 20 percent of projects and 23 percent of financing in GEF-8 (figure 10.2b). The prevalence of dual-role projects is notably higher among the regional/global coordination projects under integrated programs, largely due to the coordinating role played by the lead GEF Agency, which often also serves as the executing agency (figure 10.2c and figure 10.2d).

Dual-role arrangements are more common in global and regional projects than in national ones. For example, 36 percent of global projects—and 44 percent of associated GEF financing—involve a GEF Agency serving in both implementation and execution roles. At the national level, dual-role use varies little between LDCs/SIDS and other countries, although such arrangements are more frequent in fragile or conflict-affected situations (FCS) than in non-FCS contexts. This reflects capacity and risk considerations: many FCS countries have limited institutional capacity and few reliable local partners to serve as executors. Assigning both roles to a single experienced Agency helps manage fiduciary and operational risks; streamline oversight; and enable faster mobilization in environments where stability, security, and administrative systems are weak.

This modality is most often used by several Agencies, including the Asian Development Bank (ADB), Conservation International, the Development Bank of Southern Africa, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the International Union for Conservation of Nature, UNEP, and the World Wildlife Fund–US. Of the original three GEF Agencies, UNEP employs the dual-role approach more frequently than the others. Across different project modalities, the dual-role arrangement is more common in enabling activities, representing 11 percent of such projects and 34 percent of their GEF financing. It is also relatively prevalent in nongrant instrument (NGI) projects, accounting for 15 percent of projects and 26 percent of NGI-related GEF financing.

During implementation, a small but notable share of projects see GEF Agencies transition to a dual role. Of the 2,494 projects that began implementation, 203 (8 percent) reported a minor amendment or requested a major amendment requiring CEO endorsement or approval. Of those 203 projects, 26 (13 percent of amended projects and 1 percent of the total) adopted or proposed a dual-role arrangement. In 80 percent of the cases where such a switch occurs, the respective Agency assumes an executing role as part of a consortium (i.e., in partnership with other Agencies).

The main reasons cited in requests for amendment for transitioning to a dual role were to address capacity limitations, enhance operational efficiency, and ensure project continuity. The most common reason for dual-role transition—cited by 35 percent—was to address capacity limitations, especially in recruitment, procurement, and knowledge management. Additionally, 19 percent aimed to increase operational speed or resolve delays; 12 percent transitioned due to the withdrawal of an executing entity, requiring the GEF Agency to take on additional responsibilities to ensure project continuity.

A survey of 33 OFPs found that 70 percent supported allowing GEF Agencies to assume a dual role as both implementing and executing entity. Support varied by country group: 46 percent of respondents from LDCs and SIDS (n = 13) were in favor, compared to 85 percent from other countries (n = 20). Among supporters, 91 percent cited limited national capacity, and 52 percent pointed to challenging national contexts. About 30 percent noted other barriers, including procedural constraints, restrictions on national agencies accessing GEF funds, and small project budgets. In contrast, 30 percent of respondents opposed dual-role arrangements under any circumstances, citing concerns about conflicts of interest (70 percent), risks to national capacity development (50 percent), and threats to country ownership and sustainability (40 percent).

Stakeholder views on Agency implementation fees in dual-role arrangements are notably split, with clear differences between respondents from LDCs/SIDS and those from other countries. Under current GEF policy, Agency execution costs cannot be covered by GEF project funds and must instead come from cofinancing or national contributions (GEF 2025). When asked whether the implementation fee should be adjusted in dual-role scenarios, 65 percent of respondents believed the fee should remain the same or increase, and 35 percent favored a reduction. Among the 11 respondents who supported a fee reduction, 73 percent (8 individuals) were from LDCs/SIDS—despite this group representing only 39 percent of total respondents. In contrast, just 27 percent of fee-reduction supporters were from other countries, which made up 61 percent of the sample. These findings highlight a notable divergence in perspectives on Agency fees between LDCs/SIDS and other countries in the context of dual-role arrangements.

There is limited collaboration among GEF Agencies, which reduces opportunities for synergy, shared learning, and greater impact. The GEF currently lacks structured incentives to promote cooperation among Agencies, leading to competition—particularly within integrated programs—rather than joint effort. Survey evidence collected as part of the Eighth Comprehensive Evaluation of the GEF (OPS8) consistently points to limited collaboration as an area requiring attention (figure 10.3). The absence of institutional mechanisms to encourage joint planning and implementation has contributed to inter-Agency rivalry, especially regarding lead roles in parent and child projects. Even when GEF Agencies jointly implemented a project—as observed in several child projects under the Sustainable Cities Program—the level of collaboration among the implementing Agencies was low. Agencies tended to carry out their respective activities as separate projects, with limited coordination among them. Few stakeholders expressed strong confidence in current levels of collaboration, highlighting the need for systemic adjustments to better facilitate cooperative engagement.

Since the GEF’s establishment in 1991 with the World Bank, UNDP, and UNEP as founding Agencies, the GEF partnership has expanded in two major rounds. This expansion has broadened recipient countries’ choice of Agencies. Greater choice has also reduced the concentration of GEF Trust Fund financing. According to GEF Portal data, concentration—measured by the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index—declined from 0.50 during the pilot phase to 0.25 in GEF-4. Following the second expansion, it fell further to 0.21 in GEF-6 and reached 0.16 in GEF-8—indicating a relatively low level of concentration with financing distributed more evenly across Agencies. Each expansion has therefore been followed by a significant drop in concentration.

Agency presence remains uneven across country groups. SIDS and fragile and conflict-affected situation areas continue to have fewer GEF Agencies, with particularly limited representation in Pacific SIDS (GEF IEO 2018a, forthcoming-p). Targeted expansion measures could help address these gaps.

The STAP plays a vital role in bringing science, innovation, and technical insight into GEF operations. As the GEF’s independent advisory body, the STAP supports evidence-based decision-making through thematic papers, early-stage project reviews, and strategic advice on programs and policies. Its contributions—particularly through forward-looking thematic work on integrated programming, risk appetite, and innovation—have helped shape the direction of GEF strategies and enhance the scientific foundations of project design.

Science is at the core of the GEF’s mission. The GEF has long recognized science as a critical foundation of its work and a unique competitive advantage in the crowded field of environmental finance. Each of the conventions is deeply rooted in scientific evidence—ranging from the climate modeling of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change to the biodiversity assessments of the Convention on Biological Diversity. The conventions define global priorities based on scientific consensus and, by serving as their financial mechanism, the GEF ensures that its funding decisions are anchored in the best available knowledge about planetary systems, ecological thresholds, and environmental risks.

The STAP serves as a key channel for integrating cutting-edge scientific and technical knowledge into its operations. Established to provide independent, objective advice on GEF policies, strategies, programs, and projects, the STAP’s core responsibilities include implementing a work program developed with the GEF Secretariat and reviewing all full-size projects, preparing strategic notes for the GEF Council, flagging emerging issues, and promoting evidence-based approaches across the GEF portfolio. For instance, the STAP strongly supported the move toward integrated programs. This shift has led to initiatives that span multiple environmental focal areas—such as biodiversity, climate change, and land degradation—reflecting the scientific reality that these challenges are interconnected and must be addressed systemically.

The STAP is tasked with promoting innovation and identifying emerging tools and approaches to strengthen environmental outcomes. While its advisory role limits direct involvement in implementation, its recommendations have added value in advancing learning and improving project quality. As the GEF’s mandate expands, the STAP has increasingly engaged with complex and cross-cutting topics; this has prompted constructive reflection on how to ensure that its advice remains both scientifically robust and practically relevant across diverse country contexts.

The STAP’s role in fostering innovation is constrained by limited implementation engagement and misalignment with country realities. The STAP plays an important but limited role in promoting innovation and scale within the GEF. Its mandate includes identifying emerging tools, technologies, and cross-disciplinary approaches to enhance environmental impact, and advising on their integration into project and program design. It is expected to support adaptive learning and the development of monitoring systems to track innovation uptake. However, the STAP’s influence is constrained by its advisory role, with limited involvement in implementation or follow-up. Moreover, while its recommendations are grounded in sound science, they may not always align with country-level capacities, affecting their relevance and potential for scaling.

The STAP’s thematic papers are widely regarded as its most impactful contribution; however, concerns exist about the scope of its mandate and the burden of project reviews. STAP members themselves hold differing views on the panel’s added value, though most agree that thematic papers offer the greatest potential to shape GEF operations. These papers also inform project-level assessments. Both STAP members and stakeholders noted that the review process is burdensome and raised questions about the panel’s role in advising on topics that extend beyond its core scientific mandate. For example, issues such as risk appetite and NGIs, while relevant, may not align with the STAP’s technical expertise.

The STAP’s thematic work is broadly recognized as valuable, and many stakeholders share an interest in refining its role to keep pace with the GEF’s evolving priorities. The STAP remains a unique and valuable asset to the GEF and has played a vital role in embedding scientific and technical rigor into GEF operations, contributing significantly through thematic guidance, project reviews, and thought leadership. However, its current structure, scope, and governance need to be better aligned with the evolving needs of the GEF. Stakeholders increasingly question the STAP’s focus as it straddles the line between scientific and technical advice and operational review, with a growing share of input focused on theories of change, gender, and risk—areas beyond its core mandate. The GEF Council should initiate an update of the STAP’s terms of reference, which were last substantively revised in 2011. This revision would provide an opportunity to ensure that the panel’s structure, expertise, and work program are fully aligned with the GEF’s evolving strategic directions. Strengthening transparency, clarifying the scope and modalities of its advisory functions, and establishing a more structured performance and governance framework would enhance the STAP’s effectiveness. These measures would enable the panel to provide timely, high-quality scientific and technical input while fostering innovation in GEF programming.

.jpg)

CSOs are vital partners in the GEF’s effort to deliver inclusive, sustainable, and locally grounded environmental solutions. Their knowledge of community priorities, ability to build trust, and practical experience in mobilizing grassroots participation position them as key actors across the GEF portfolio. From project design to implementation and monitoring, CSOs help ensure that interventions are responsive to local needs and more likely to deliver lasting results.

The GEF’s Small Grants Programme demonstrates the potential of direct civil society engagement, supporting thousands of CSOs—often led by women, youth, and Indigenous Peoples—in developing community-based solutions. These initiatives frequently extend beyond project boundaries to strengthen local institutions, improve livelihoods, and catalyze behavioral change.

Beyond project delivery, CSOs play an important role in shaping inclusive processes, promoting gender equality, and enhancing transparency. In countries such as Indonesia and Peru, civil society engagement in project planning and social analysis has helped align initiatives with local dynamics and strengthened social outcomes. In other cases, CSOs have acted as accountability agents—helping mediate community concerns and resolve implementation challenges, as seen in countries such as Bolivia and Ghana.

The GEF-CSO Network complements the role of other GEF entities by linking grassroots experiences to global governance. Through its participation in expanded constituency workshops and regional dialogues, the network contributes to policy discussions and fosters stronger connections between CSOs, governments, and OFPs. However, its reach and influence remain uneven across regions, constrained by structural and resource limitations.

There are clear opportunities to strengthen the GEF’s partnership with civil society. CSOs are often engaged late in the project cycle, limiting their ability to influence upstream design and strategy. Administrative requirements and funding barriers can further restrict the participation of smaller or underrepresented groups. Stakeholders note a gap between community‑based approaches—typically designed by external actors and implemented with community participation; see chapter 7 for more detail—and community‑led ownership, where initiatives are originated, designed, and managed by the community itself. Bridging this gap could enhance local ownership, equity, and long‑term sustainability of GEF-supported initiatives.

GEF-8 acknowledges these challenges and seeks to enhance CSO participation across the full project cycle—from planning and co-design to implementation and monitoring. Initiatives such as the GEF’s Ecosystem Restoration Integrated Program are beginning to reflect this shift. At the same time, complementary roles for government remain essential—especially in areas requiring policy reform, such as land tenure and legal frameworks.

Ultimately, civil society is a crucial pillar of the GEF partnership. Strengthening this collaboration through earlier engagement, clearer roles, and more accessible resources will be key to delivering on the GEF’s commitment to inclusive, locally led environmental action.