The GEF’s donor base has been shrinking and becoming more concentrated over time, with a smaller group of donors providing an increasing share of total contributions. While core support remains strong, this concentration increases the risk of funding volatility and reduced predictability—particularly if one or more major contributors reduce or delay their pledges. These trends highlight the importance of diversifying and broadening the donor base to strengthen financial resilience and sustain long-term programming.

The GEF Trust Fund has been primarily supported by a stable core of sovereign donors. Recent patterns point to a gradually contracting and increasingly concentrated donor base, with limited diversification in recent replenishments. Since GEF-5, six countries—France, Germany, Japan, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States—have ranked among the top five contributors to the GEF Trust Fund at least once. Germany and Japan have consistently remained in the top three contributors across all replenishments from GEF-5 to GEF-8, while the United States has done so in all but GEF-7. Sweden has steadily increased its share, moving from the seventh-largest contributor in GEF-5 to a more prominent position in subsequent replenishment periods. Beyond the GEF Trust Fund, Canada is the largest contributor to the GBFF and the third-largest donor to the SCCF. Belgium is the second-largest contributor to the LDCF and the fourth-largest to the SCCF.

Of the 34 countries that have contributed to the GEF Trust Fund at least once since GEF-5, 28 have participated in all four replenishments. At the same time, the total number of donors declined from 33 in GEF-5 to 29 in GEF-8, with five countries not returning for the latest period. Côte d’Ivoire is the only country to have joined as a new donor in recent years, contributing in GEF-7 and GEF-8. The number of recipient donors—countries that contribute while also receiving GEF funding—has declined from eight in GEF-5 to six in GEF-8, and their share of total contributions has dropped from 3.7 percent to 2.7 percent. No countries from the Middle East and North Africa have contributed to the GEF Trust Fund, although several, including Qatar and the United Arab Emirates, have pledged resources to other climate funds such as the GCF and the Adaptation Fund. Similarly, some GEF participant countries—including Latvia, Mongolia, Poland, and the Slovak Republic—have contributed to other climate mechanisms but not to the GEF since GEF-5. The LDCF has received contributions from five countries that have not contributed to the GEF Trust Fund: Estonia, Hungary, Iceland, Qatar, and Romania. Both the LDCF and the GBFF have received contributions from subnational entities, although these remain very limited: about 1.4 percent for the LDCF and 1 percent or less for the GBFF of their total pledges.

Unlike other global funds, the GEF does not tap into a network of philanthropic foundations. Organizations such as the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria have successfully incorporated the private sector and philanthropic organizations into their donor bases. While sovereign donors remain the most significant source of funding in all global funds, stronger engagement with nonsovereign donors could lead to more private sector engagement, opportunities for scaling up innovations, and avoid a decline, in real terms, in the GEF’s funding base.

.JPG)

Introduced in 2010, the STAR allocates GEF funding to eligible recipient countries for the biodiversity, climate change, and land degradation focal areas. Other focal areas and special initiatives—such as international waters, chemicals and waste, the Least Developed Countries Fund, and the Special Climate Change Fund—operate outside its scope. Under GEF-8, national ownership was strengthened by granting countries full flexibility to reallocate STAR funds across focal areas according to their priorities, supporting more strategic and long-term planning. Additional changes included raising the focal area country allocation floors for LDCs and SIDS, lowering the country allocation ceiling from 10 percent in GEF-7 to 6 percent in GEF-8, and increasing the weight of the gross domestic product (GDP) index. These adjustments enhanced ex ante allocations to priority countries.

Recipient countries widely recognize the predictability of STAR resources as a key comparative advantage of the GEF, particularly for those with capacity constraints or challenging circumstances. In GEF-8, 39 percent of STAR allocations went to LDCs and SIDS, while countries in fragile and conflict-affected situations received 20 percent. A 2025 IEO stakeholder survey conducted as part of the competitive advantage study of the GEF (GEF IEO 2025a) found that the STAR is widely perceived as being fair in allocating GEF resources. However, channeling resources through the STAR can lead to fragmentation. To address this issue, GEF-8 allows countries full flexibility to use STAR resources across eligible focal areas, enabling interventions at scale.

The GEF’s reliance on the STAR to provide resources for programming has declined, with the STAR’s share of total GEF Trust Fund allocations dropping from 53 percent in GEF-6 to 46 percent in GEF-8. This reduction is mainly due to decreased climate change allocations and a larger share directed to set-asides, especially for integrated programming. While this trend reduces the volume of predictable resources available to eligible countries, it increases the GEF’s flexibility to deliver activities at an appropriate scale.

In addition to contributions from sovereign donors, the GEF seeks cofinancing as a means to increase its environmental impact, expand project activities, and strengthen partnerships. The evaluation of cofinancing in the GEF (GEF IEO 2025b) examined the effectiveness of the GEF’s cofinancing strategy, comparing it with that of other organizations and assessing how the GEF mobilizes cofinancing and how its executing partners manage it. The evaluation also explored factors influencing funding commitments and their realization.

The GEF sets ambitious cofinancing targets, with an overall portfolio target of $7 for each dollar of GEF funding, that is, a 7:1 cofinancing ratio.2 For investment cofinancing in upper-middle-income or high-income countries that are not SIDS, the target is 5:1. In comparison, the International Fund for Agricultural Development has a target of 1.2:1, while Gavi’s cofinancing requirements range from 0.25:1 to a maximum of 9:1. Notably, the Global Fund, the GCF, ADB, and the World Bank do not specify cofinancing targets.

The GEF’s approach to cofinancing is flexible, allowing for a broader range of contributions than institutions such as ADB and the World Bank. Unlike several other organizations, the GEF accepts in-kind contributions and considers country context when setting cofinancing expectations. Additionally, it provides exceptions in emergencies or unforeseen circumstances, ensuring adaptability in its financing model.

The GEF’s flexible approach to cofinancing enables high fund mobilization but raises concerns about the credibility of reported cofinancing. Its broad definition allows for high reported cofinancing ratios, although not all contributions are equally essential. To improve cofinancing quality, considerations such as the time value of money, likelihood of realization, alignment with GEF-funded activities, and the extent to which cofinancing is critical to achieving project objectives are important.

The GEF Agencies use different strategies to raise cofinancing. Multilateral development banks mostly use internal resources, adjusting their cofinancing strategies based on the required level of concessional finance and whether the project involves a loan investment or an advisory product. UN organizations and INGOs take a proactive approach to securing cofinancing, relying more on in-kind and parallel cofinancing sources.

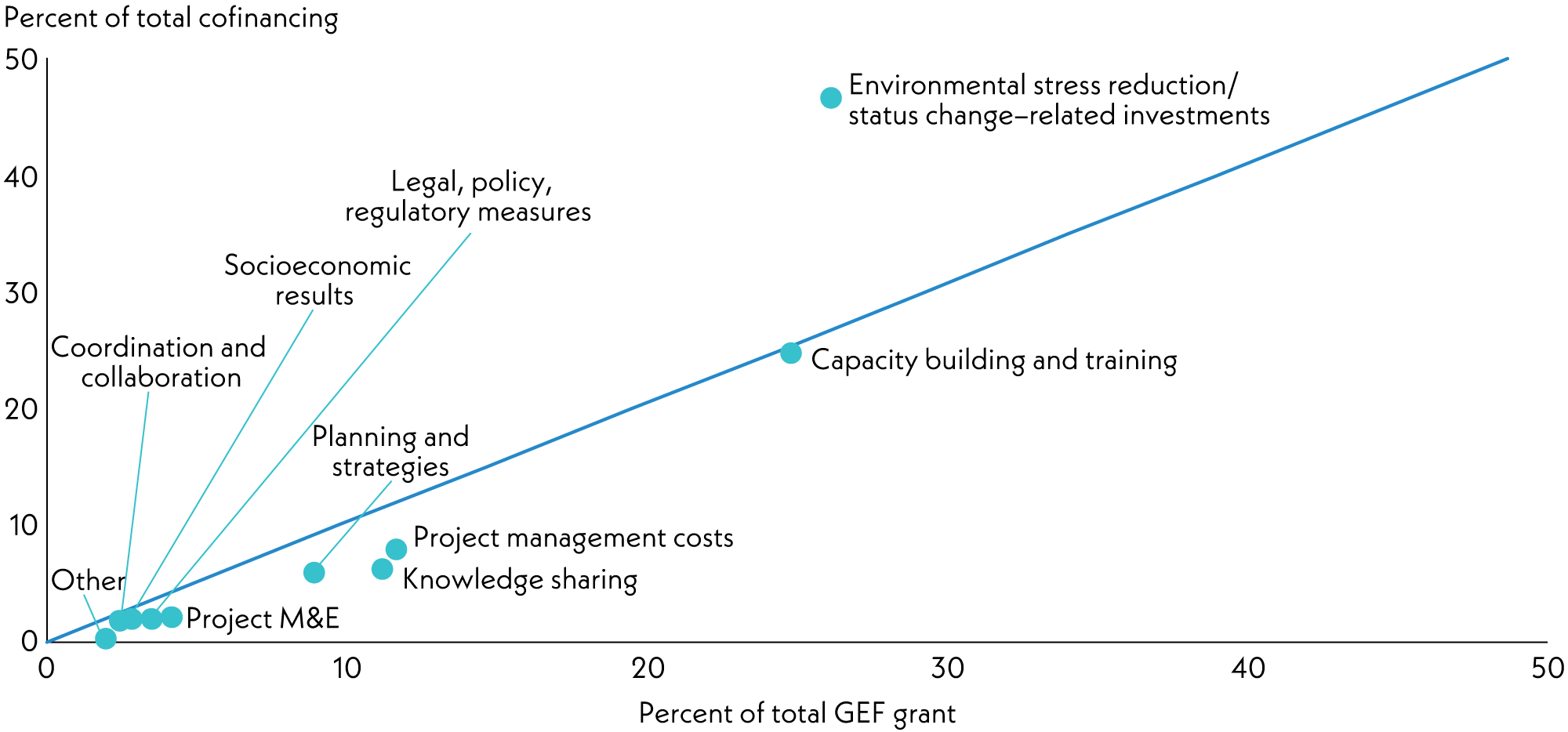

The level of cofinancing commitments for a project is influenced by its design components. Project components that directly reduce environmental stress or improve environmental conditions typically attract higher levels of cofinancing (figure 10.4). These include infrastructure development, technology demonstration, and the procurement of efficient equipment and vehicles. In contrast, activities such as capacity building, legal and policy development, and project monitoring generally receive lower levels of cofinancing.

From GEF-6 through GEF-7, GEF projects secured cofinancing commitments averaging $7.50 for every dollar across all GEF-managed funds. Between GEF-6 and GEF-7, projects attracted an average of $7.70 in cofinancing for every dollar of GEF funding. However, only half of the projects fully met their cofinancing targets, with lower realization in LDCs and SIDS. Projects funded through the GEF Trust Fund generally raise higher levels of cofinancing compared to those funded through the Capacity-building Initiative for Transparency, the Least Developed Countries Fund (LDCF), and the Special Climate Change Fund (SCCF).3 Projects in the climate change mitigation and international waters focal areas, as well as national and regional projects, tend to attract higher levels of cofinancing commitments. Conversely, projects focused on biodiversity conservation, those with a global scope, and those implemented in LDCs and SIDS generate lower levels of cofinancing.

On average, GEF projects achieve their expected level of cofinancing, although realization rates vary by country context and Agency type. A review of project documents for 118 completed GEF-6 and GEF-7 projects found that cofinancing realization at completion averaged 102 percent of the committed amount. Realization tends to be lower in LDCs and SIDS, while projects in upper-middle- and high-income countries (excluding SIDS) achieve higher realization rates (figure 10.5). Additionally, cofinancing realization for projects implemented by multilateral development banks is lower compared to those implemented by UN and other entities, with underreporting cited as a contributing factor.

Thirty-four percent of cofinancing commitments (number, not total amount) in project proposals are not realized, and GEF Agencies fill this gap by securing new sources of cofinancing. The shortfall is most pronounced among loans—55 percent of which go unrealized—followed by 32 percent of grants and 34 percent of in-kind contributions. Loan realization is especially vulnerable to shifts in national priorities and delays in project execution, frequently resulting in reductions or cancellations. Projects implemented by multilateral development banks face particular challenges due to their reliance on loan financing, while INGOs fulfill less than half of their cofinancing commitments. Among the cofinancing contributions realized by project completion, 40 percent come from new sources. UN entities and INGOs actively seek alternative cofinancing during implementation, often in response to midterm review findings, although options remain limited for projects in SIDS because of the smaller pool of potential contributors.

Full realization of cofinancing commitments shows a positive correlation with both outcome and sustainability ratings. When projects fully realize expected cofinancing, the outcome rating increases by 0.10 points on a binary scale and 0.30 points on a six-point scale. Similarly, the likelihood of sustainability is rated 0.23 points higher on a binary scale and 0.33 points higher on a four-point scale for projects with full cofinancing realization. Qualitative analysis indicates support for a positive causal relationship between cofinancing realization and outcome achievement.

Proportionality in project management costs between cofinancing and GEF financing is a recurring issue in GEF Secretariat feedback to Agencies, often resulting in extensive exchanges. The GEF’s Rules and Guidelines for Agency Fees and Project Management Costs stipulate proportionality in these costs (GEF 2010). However, with in-kind cofinancing present in 84 percent of GEF projects and parallel cofinancing frequently used, Agencies struggle to meet proportionality requirements. This challenge arises because much of the cofinancing—both in-kind and parallel—is not managed by the project’s management unit, making it difficult to allocate a proportionate share of project management costs across the full cofinancing amount. Consequently, reviewers identify discrepancies and gaps related to proportionality in 60 percent of proposals.

Tracking and reporting of cofinancing commitments have improved, but challenges remain in verifying the realization of these commitments. Tracking and reporting of cofinancing commitments have improved as a result of updated policies and the adoption of the GEF Portal, which offers real-time aggregated data. However, verifying the actual realization of cofinancing remains challenging. Persistent issues include incomplete documentation, difficulty tracking in-kind contributions, and limited information in midterm reviews and terminal evaluations. While the GEF Secretariat emphasizes compliance during project preparation, it relies largely on Agency-reported data, with minimal follow-up to confirm accuracy or completeness.